#771) Cicero March (1966)

Filmed by Mike Shea and Mike Gray

Class of 2013

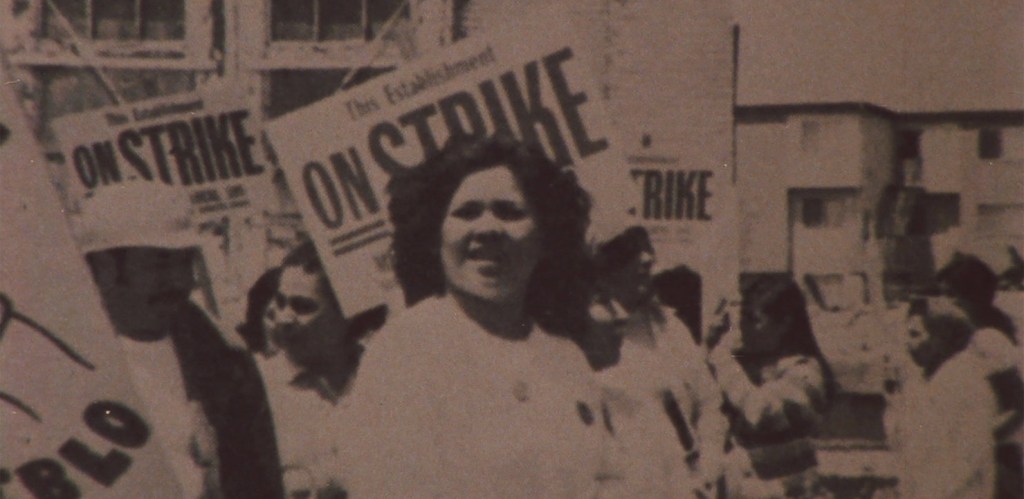

In the summer of 1965, Civl Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., activist James Bevel, and Chicago teacher Al Raby joined forces to create the Chicago Freedom Movement (CFM) in an effort to end racial discrimination practices in Chicago’s housing, education, and employment systems. The CFM’s non-violent marches were met with extreme hostility from Chicago’s predominantly White population, with Dr. King calling the attacks on these marches worse than similar altercations he had experienced in the south. Following a particularly violent march in July 1966, Dr. King met with Chicago city leaders the following month and reached an agreement for the city to enforce desegregation and open-housing laws, on the condition that King not attend a planned march in the all-White suburb of Cicero that September. Although the CFM withdrew their plans for the Cicero march, the Chicago branch of the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE), unhappy with King’s agreement with the city, didn’t back down. On Sunday September 4th, 1966, CORE Chicago chapter leader Robert Lucas led 250 protesters on a march through Cicero, where they were met by escalating jeers from the White citizens. Among the protestors were filmmakers Mike Shea and Mike Gray of The Film Group, capturing the chaos of the day cinema verité style with a single camera. “Cicero March” is the only known footage documenting what happened that day, an event that inched America closer to the Civil Rights Act of 1968 (aka the Fair Housing Act).

In a brief eight minutes, “Cicero March” puts you in the middle of the proceedings, watching the seething racism of the White citizens, the struggles of the Black marchers to keep the peace, and the presence of countless police officers reach their natural boiling point. “Cicero March” is an unflinching account of an oft-overlooked chapter in Civil Rights history, giving you a true sense of what it must have been like to be there. As unsettling as it is watching this racist vitriol spewed in real time (and recognizing how little has changed in 60 years), I’m glad the NFR has found a place for “Cicero March” and the Cicero marchers among its ranks.

Why It Matters: The NFR write-up is a recap of the events leading to the march, and includes an essay by Chicago Film Archives founder Nancy Watrous.

Everybody Gets One: Founded by Mike Gray and Jim Dennett in 1964, The Film Group spent most of its decade-long existence specializing in local TV commercials and industrial shorts. There was the occasional dabble with something more experimental or au courant, and the Cicero march of 1966 was seen by the Film Group as an opportunity to get more documentary experience between gigs. Gray brought along The Film Group’s recently-hired photographer Mike Shea to the march, where Shea handled the film camera while Gray recorded sound.

Seriously, Oscars?: No Oscar nod for “Cicero March”. For the record, the 1966 Oscar for Best Documentary Short went to the more high-profile “A Year Toward Tomorrow”, narrated by Paul Newman and championing the recently founded Volunteers in Service to America (now known as AmeriCorps VISTA).

Legacy

- Immediately after the march, Shea and Gray returned to The Film Group and gave the footage to their intern/editor Jay Litvin. Though initially shelved, “Cicero March”, was later incorporated into a seven part educational series by the Film Group called “The Urban Crisis and the New Militants”, consisting primarily of footage shot during the 1968 Democratic Convention riots. Following the Film Group’s closure in 1973, “Cicero March” (and most of The Film Group’s library) was donated to the Chicago Public Library’s film collection.

- In 2005, a print of “Cicero March” was donated to the Chicago Film Archives by Film Group member William Cottle, and was preserved by the Archives with grants from the National Film Preservation Foundation. After being nominated for NFR consideration by the Archives in 2006 and 2008, third time was the charm for “Cicero March” in 2013, shortly after the death of Mike Gray that April.

- Of the Film Group group, Mike Gray seems to have had the most prolific career, most notably co-writing the screenplay for 1979’s “The China Syndrome”. We’ll see more of Mike Gray and The Film Group went I get around to covering their other NFR entry: “The Murder of Fred Hampton”.