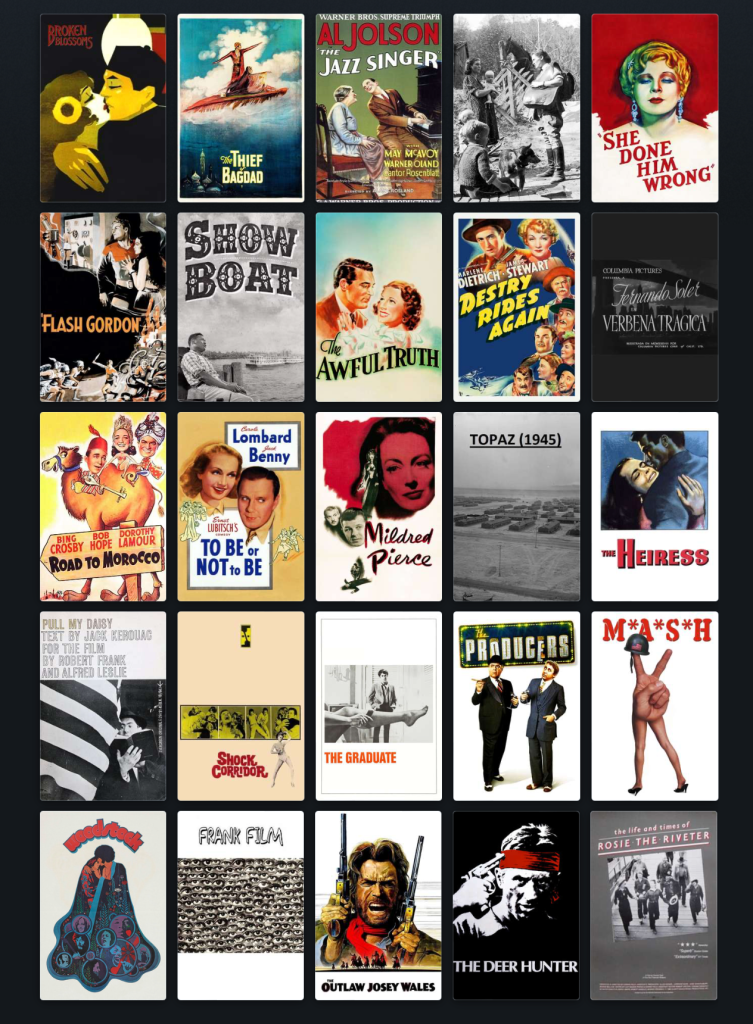

December 2nd 1996: As Americans were fighting each other Battle Royale style to buy any remaining Tickle Me Elmos, the NFR announced their next batch of inducted movies, bringing their total to 200 significant American films. Here are those 25, plus a few blurbs from my write-ups:

- Broken Blossoms (1919): “Have we all gone insane?…anyone who says [‘Broken Blossoms’] is one of the greatest films ever made needs to get their head examined.”

- The Thief of Bagdad (1924): “the quintessential Douglas Fairbanks epic”

- The Jazz Singer (1927): “will always have a place in the annals of film history, but…it’s remembered more as an antiquated relic than as a piece of entertainment.”

- The Forgotten Frontier (1931): “a fascinating historical document”, “lets [sic] give nurses three cheers…and significantly higher pay.”

- She Done Him Wrong (1933): “on here for Mae West…one of Hollywood’s most important stars.”

- Flash Gordon (1936): “if you’re going to include one film serial on your Registry, this is the one.”

- Show Boat (1936): “a breakthrough in its day, but its problematic story beats have caused it to age poorly.”

- The Awful Truth (1937): “an entertaining rom-com and a prime example of Classic Hollywood filmmaking.”

- Destry Rides Again (1939): “an underrated gem…that gets lost in the shuffle of classic westerns”.

- Verbena Tragica (1939): “represent[s] the long-lost practice of Hollywood studios filming multiple versions of the same movie in different languages.”

- Road to Morocco (1942): “The ‘Road’ movies were popular enough and have a long enough legacy to warrant NFR inclusion, but at this point the film is being held up on its reputation.”

- To Be or Not To Be (1942): “a thoroughly funny movie”, “both a satirical farce and a dark reportage of a country caught in war.”

- Topaz (1943-1945): “Having actual footage from one of the [Japanese] internment camps is a near-miracle.”

- Mildred Pierce (1945): “not one of the essentials, but overall it is still a pretty damn good film.”

- The Heiress (1949): “an entertaining film made by A+ talent.”

- Pull My Daisy (1959): “I don’t get this Beat stuff”

- Shock Corridor (1963): “What the fuck did I just watch?”

- The Graduate (1967): “might not capture the zeitgeist of the late ‘60s, [but] its examination of young adulthood’s uncertainties is timeless.”

- The Producers (1967): “a landmark in film comedy”, “led the way for the zany masterwork of Mel Brooks.”

- MASH (1970): “I’ll be curious to see if the film continues to hold up compared to the TV series.”

- Woodstock (1970): “an immersive, unforgettable movie about a landmark American event.”

- Frank Film (1973): “just as worthy of NFR recognition as any of the other crazy shorts on the list.”

- The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976): “a well-crafted encapsulation of [Clint Eastwood’s] strengths as actor and director.”

- The Deer Hunter (1978): “Well that was thoroughly depressing”, “well made…but I don’t need to watch it again anytime soon.”

- The Life and Times of Rosie the Riveter (1980): “a compelling examination of an underrepresented era of woman”.

Other notes

- As mentioned in my Class of ’95 post, the National Film Preservation Act got renewed in May 1996 through 2003. This reauthorization also established the National Film Preservation Foundation, with an initial goal to preserve smaller films like educational shorts, “orphan” films, and films in the public domain. According to a Variety article at the time, the first donation to the National Film Preservation Foundation was from Martin Scorsese for $25,000. Speaking of finances, part of the NFR’s 1996 reauthorization cut its funding down from two million dollars a year to $250,000 a year (and bumped down the proposed extension from 10 years to 7). This is back when Republicans were blaming Hollywood for all of society’s ills, so I’m sure that didn’t help matters. Damn you, Senator Bob Dole!

- Taking in all 25 of these movies, the emphasis seems to be on movies of their time, especially if those times are during World War II or the late ‘60s/early ’70s. Most of these films have a real sense of time and place, from the recreated time and place of period pieces to the literal time and place of documentaries. Yes, a lot of these films cover the same time periods, but like so many of these early NFR inductions, you have less than a century of American film to cull from, and the essentials have almost all been selected by the eighth round. As the years go on, both the timespan and subject matter of these films will diversify.

- My writings on these films are mostly positive; I can justify each one’s Registry status without too many caveats, even the ones I didn’t like. What struck me in re-reading my posts was how political these write-ups are. Part of that is the political nature of some of these movies (1996 was an election year, so I guess politics were on the Board’s mind), but a lot of it is the political times I was writing them in. We have lived through a lot of history since 2017 – the Trump presidency, the Me Too movement, COVID, the Trump presidency again – so some of that is going to bleed into my writing. Heck at one point I even reference “bone spurs”. Deep cut, 2017 Me, deep cut.

- When the Class of 1996 was announced, the live-action remake of “101 Dalmatians” was #1 at the US box office. Other noteworthy films playing in theaters that week include “Space Jam”, “The English Patient”, “Romeo + Juliet”, “The First Wives Club”, “Independence Day”, and “Mission: Impossible”. This is the first year where, as of this writing, no film playing in theaters the week of an NFR induction have entered the NFR (“Fargo” had already played theaters that spring and “The Watermelon Woman” wouldn’t receive a theatrical release until 1997).

- This year’s Double-Dippers include actors Jack Carson, Irene Dunne, Cary Grant, and Charles Winninger, costume designer Edith Head, and cinematographer Hal Mohr. My notes also include “Queen of the Background Extras” Bess Flowers, but she’s on this list practically every year.

- Thematic Double-Dippers: The aforementioned eras of WWII and the late ‘60s, radio comedians turned movie stars, Olympic athletes turned actors, extra-marital affairs, future sitcom stars, beatniks/hippies, plays making fun of Hitler, tense family dynamics, whitewashed casting, intermittent loudspeaker announcements, shoehorned musical numbers, and a whole lotta race issues grossly mishandled by White creatives.

- Favorites of my own subtitles: Come What Mae, Battle of the Exes, Bad Harem Day, Spying is Easy Comedy is Hard, Bridge Over Troubled Daughter, That’s Not Filming It’s Typing, How Do You Solve a Problem Like Korea?, and The Best Fucking Years of Our Fucking Lives

Alright, whattya got, Class of 1997? You’re next.

Happy Viewing,

Tony