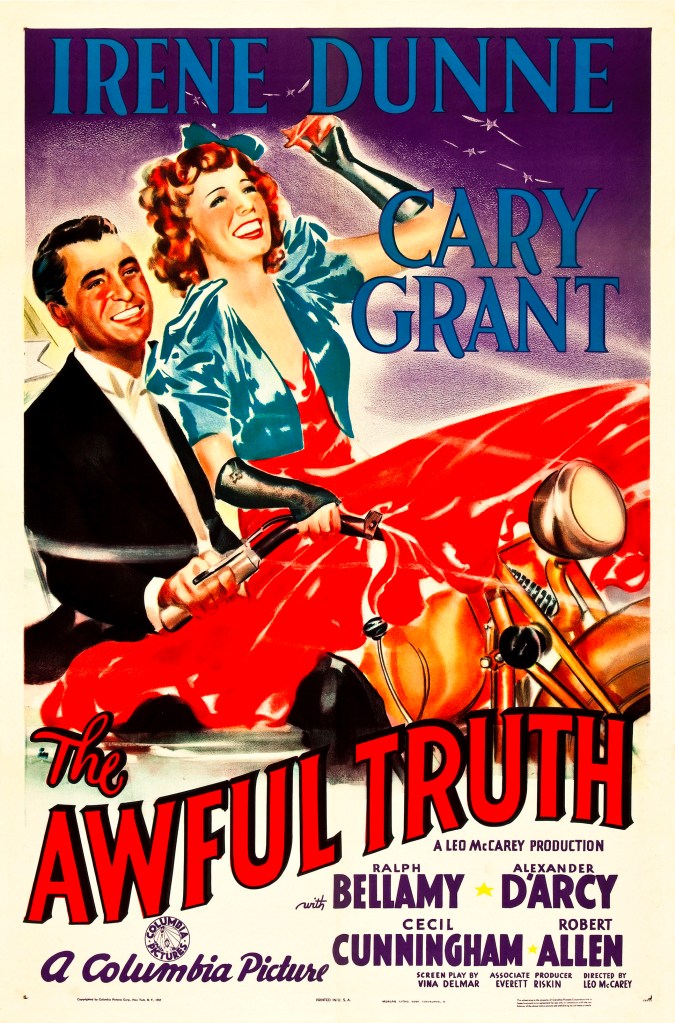

#671) The Awful Truth (1937)

OR “Battle of the Exes”

Directed by Leo McCarey

Written by Viña Delmar. Based on the play by Arthur Richman.

Class of 1996

The Plot: Jerry and Lucy Warriner (Cary Grant and Irene Dunne) are a sophisticated, urbane married couple with increasing paranoia about the other’s infidelities. Having enough, the two file for divorce, only fighting for custody of their dog, Mr. Smith (Skippy). A 90-day interlocutory period is enforced before the divorce is finalized, and the Warriners begin seeing other people. Lucy starts a courtship with Midwest oilman Dan Leeson (Ralph Bellamy), while Jerry finds himself in a whirlwind romance with heiress Barbara Vance (Molly Lamont). But of course Lucy and Jerry can’t help but interfere in each other’s business, with plenty of antics and mishaps until these two realize the awful truth.

Why It Matters: The NFR calls it “one of the funniest of the screwball comedies”, and gives a quick overview of its plot and production history.

But Does It Really?: Oh sure. “The Awful Truth” isn’t the definitive screwball comedy, but it’s certainly up there. The film holds up surprisingly well for an 86 year old movie, still packing in plenty of laugh-out-loud moments thanks in part to the undeniable chemistry of its two leads (and their dog). While most of this film’s contemporaries are becoming historic artifacts, “The Awful Truth” remains an entertaining rom-com and a prime example of Classic Hollywood filmmaking.

Wow, That’s Dated: The big one is the interlocutory period for the Warriner’s divorce. While some states still require a “cooling-off” period, most states have done away with interlocutory periods as they rarely helped with a couple’s reconciliation and wasted everyone’s time. That being said, my research found this recent article about how hard/dangerous it is for women to get divorced in America. Perhaps we haven’t progressed as much as we would like to think we have.

Seriously, Oscars?: One of Columbia’s biggest hits of the year, “The Awful Truth” received six Oscar nominations, including Best Picture. The film lost most of its noms to “The Life of Emile Zola“, but took home one trophy: Best Director for Leo McCarey (who allegedly told the crowd that he won for the wrong movie). Irene Dunne’s Best Actress nomination was the third of her eventual five losses in the category, and Ralph Bellamy’s Best Supporting Actor nomination was the only one of his career (Bellamy would eventually receive an honorary Oscar 49 years later).

Other notes

- The stage version of “The Awful Truth” premiered on Broadway in 1922 and was an immediate hit. Two film versions followed; a 1925 silent film and a 1929 talkie. The film rights found their way over to Columbia by the late 1930s, and Harry Cohn assigned directing duties of another remake to Leo McCarey – freshly hired at Columbia after being freshly fired from Paramount. McCarey hated the script and previous film versions, but felt the concept had potential to be a hit with Depression era audiences. The script had multiple rewrites (including one by Dorothy Parker), but in the end McCarey threw out practically every draft and created the final film through extensive improvisation with his actors. Cary Grant initially balked at the idea of ad-libbing and pleaded to be taken off the picture, but he eventually warmed up to the idea, quickly becoming by many accounts the cast’s quickest and funniest improviser. “The Awful Truth” was filmed over six weeks in summer 1937 and released that October.

- As previously mentioned, the film’s biggest selling point is its stars. Cary Grant is, of course, very Cary Grant in this movie, but it still feels organic and befitting the character. This is my first time covering Irene Dunne for the blog and I was thoroughly charmed by her. Like Cary Grant, Dunne seems so comfortable in this role, gamely tossing out her one-liners and not afraid to be the clown when the scene calls for it. Their talents complement each other on screen, which leads to their believable relationship and therefore a believable movie.

- I never realized how much of this movie revolves around the dog. That’s Skippy, better known as Asta in the “Thin Man” film series, and he is being put to work playing some very specific sight gags (I noticed the “hide and seek” shot gets reused a couple times in that scene). During production Skippy was owned/trained by Gale Henry East, a former silent comedy star who spent her later years training dogs with her husband Henry East.

- One familiar looking character to me was Armand, Lucy’s voice teacher and possible lover played by Alexander D’Arcy. His suave looks and stiff acting reminded me of the guy who played Gary in the schlocky ’50s movie “Horrors of Spider Island”. Further research concluded that Alexander D’Arcy IS the guy who played Gary in “Horrors of Spider Island”. It amazes me how many people on the NFR have a connection to at least one “Mystery Science Theater 3000” movie.

- Ralph Bellamy is the perfect third wheel; his Dan is different enough from Jerry to be a believable alternative for Lucy, but never quite charming enough to be a serious threat. Bellamy will continue his character work as the amiable fiancé of Cary Grant’s ex in another classic of the era: “His Girl Friday“.

- My favorite scene in the film hands-down is when Jerry and Lucy run into each other at the nightclub. Jerry has the upper hand for most of the scene, and is delightfully dickish, literally waltzing into frame to ruin Lucy’s night out with Dan. His final line to the waiter may be my favorite in the whole movie. The only part of the scene that didn’t work for me was the shoehorned musical number: “My Dreams Are Gone With the Wind”, an obvious reference to the then-wildly popular novel, soon to be a major motion picture.

- It’s always fun watching Cary Grant do his own stunts. Grant started off his showbiz career as a tumbler with an acrobatic troupe, so the pratfalls Jerry does while at Lucy’s recital came naturally to Grant.

- Movies from the ’30s always feel like they were filmed in an alternate dimension: everything appears normal, but the attitudes of the day are foreign to a modern audience. “Awful Truth” shows how different courtship was back then: Dan’s been dating Lucy for a few months and they haven’t even kissed yet? Hard to believe there was a time in this country when we were even more prudish.

- The last comic highlight for me was Lucy showing up as Jerry’s sister to ruin his engagement. After that the movie runs out of steam as they wreck his car, get involved with the police, and spend the night at her Aunt Patsy’s cabin. We know these two are going to end up back together, but it feels weirdly unfulfilling. And what is the deal with that clock? Why did they use real people instead of just making an actual clock? Did Columbia force this movie to use their Effects department?

Legacy

- “The Awful Truth” was both a financial and critical success upon release, and easily made the transition from hit movie to classic. Although “Awful Truth” still gets mentioned in any rundown of screwball comedies, it rarely gets singled out for any specific line or moment, other than its title, which still gets alluded to in pop culture (notably as the title of many a TV episode).

- Leo McCarey’s next movie was another classic: 1939’s “Love Affair” (which still somehow hasn’t made the NFR). McCarey would win his second Best Director Oscar in 1944 for another NFR movie: “Going My Way“.

- Cary Grant and Irene Dunne got along famously during filming and would reunite for two more movies: 1940’s screwball “My Favorite Wife” and 1941’s melodrama “Penny Serenade”, the later earning Grant his first Oscar nomination. The pair would reprise their roles from “The Awful Truth” one more time for a 1955 episode of Lux Radio Theatre.

- “The Awful Truth” got one more film adaptation: the 1953 musical “Let’s Do It Again” starring Ray Milland and Jane Wyman. Not a remarkable film, but a bit in which Milland puts on the wrong hat (also done by Cary Grant in the ’37 version) inspired writer Richard Matheson to write his novel “The Shrinking Man”, which shortly thereafter became fellow NFR movie “The Incredible Shrinking Man“.

- Perhaps the biggest influence “The Awful Truth” had on film history was the solidification of Cary Grant’s screen persona. Grant had been coming into his own as a film actor over the previous five years, but “Awful Truth” brings it all together in one performance: sophisticated and charming, while simultaneously funny and physical. Aside from less stunt work, Grant rarely strayed from this persona for the rest of his career.

7 thoughts on “#671) The Awful Truth (1937)”