“…Timmonsville…Whitmire…Winnsboro…Woodruff…York.”

Jesus, that took forever. Okay, what’s next?

#769) Chelsea Girls (1966)

OR “One Film, Two Film, Red Film, Blue Film”

Directed by Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey

Written by Warhol and Ronald Tavel

Class of 2024

The Plot: Filmed at the iconic bohemian hotel in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood, “Chelsea Girls” is twelve segments, each presented in one uncut 30 minute take, showcasing life in the Hotel Chelsea as depicted by a cast of Andy Warhol’s “Superstars”. Adding to Warhol’s trademark experimentation, the segments are projected side-by-side, with sequences overlapping each other in an attempt to capture the spontaneity and volatility of an artist community. But if you really want to know what this film is about, I would describe it as 194 minutes of my life I’m never getting back. Strap in kids, this one’s a doozy.

Why It Matters: The NFR claims that the film (which they call “The Chelsea Girls”) “encapsulates everything that makes a Warhol a ‘Warhol’”, praising it as “a time capsule of a downtown New York art scene that is long gone but not forgotten.”

But Does It Really?: Given the size of his pop culture footprint, I like that Andy Warhol has two films on the Registry…in theory. In practice, watching “Chelsea Girls” was one of the most irritating, unpleasant viewing experiences I’ve had for this blog. Nothing about this film worked for me: not the acting, not the scenarios, even the experimental juxtaposition wore thin on me, ultimately coming across as more “gimmicky” than anything else. In my previous Warhol post, I distilled his art down to the phrase “look closer”. If we apply this mantra to “Chelsea Girls”, I have looked closer at Warhol’s scene in its prime, and I hate it with a burning passion. I will allow “Chelsea Girls” on the NFR, but unless you’re really into Warhol and that era of pop art, you can skip this one.

Everybody Gets One: Co-director Paul Morrissey had already made a name for himself as a filmmaker and operator of the Exit Gallery cinematheque in the East Village when he met Andy Warhol in 1965. Impressed with his work, Warhol invited Morrissey to collaborate with him on his film “Space”, the first of 11 films Morrissey made with Warhol at The Factory. Morrissey continued making low-budget films on his own in the ‘70s and ‘80s, and in his later years resented how much credit Warhol took for their collaborations. Less is known about this film’s co-writer Ronald Tavel, who spent most of his career as an Off-Broadway playwright specializing in what became known as “Theatre of the Ridiculous”.

Title Track: Since the film has no opening or closing credits, it is alternatively known in different write-ups and reviews as “Chelsea Girls” and “The Chelsea Girls”. Much like my “20/Twenty Feet from Stardom” conundrum, I’ve made my choice, ditched the “The” and gone with “Chelsea Girls”. It’s cleaner.

Other notes

- The Hotel Chelsea opened as a co-op in 1884, and from the onset attracted artists as tenants due to its proximity to several theaters in the Chelsea neighborhood. By the early 1960s, the building had been converted into an apartment hotel (with its initial 100 rooms broken up into almost 400), and like its surrounding neighborhood, had fallen on hard times. It was around this time that the hotel started renting rooms to several artists associated with Warhol’s Factory, as well as rock stars not allowed to stay at other hotels. In 1966, a few months before “Chelsea Girls” started filming, the Hotel Chelsea was named a historic New York landmark.

- Andy Warhol conceived of what became “Chelsea Girls” in the summer of 1966. Warhol’s initial idea was a film split down the middle, with “all black on one side and all white on the other.” This concept would evolve into a more figurative interpretation in the final film, with the tone of each segment alternating between “lighter” and “darker”. Although Warhol had a specific order the segments would play in, projectionists were allowed to switch the audio from one to another at will, making each viewing of “Chelsea Girls” a unique experience.

- In an attempt to streamline these notes, we are pairing up the film segments that spent most of their screen time in my viewing side by side. Titles are listed as they appeared on the screen from left to right.

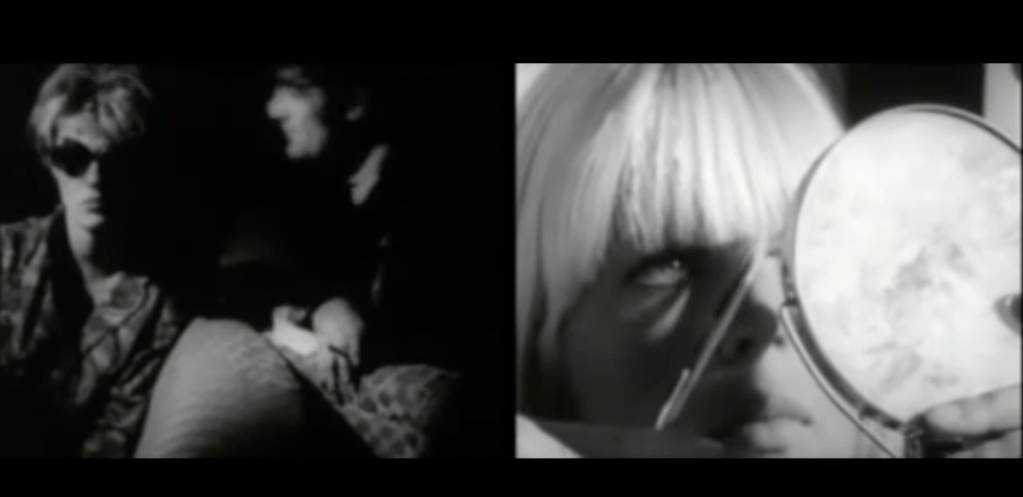

Father Ondine and Ingrid/Nico in Kitchen

- On your left is actor Ondine claiming to be a priest while having an inappropriate conversation with Ingrid Superstar. On your right is German supermodel Nico fixing her hair in her kitchen while spending time with her son Gerard. We are off and running with what to expect from this film, with your initial choices being either grating, amateur improv or mundane minutiae with no sound. Is there a third choice?

- The sound in this film is terrible. I doubt that anyone is miked, which means unless you project, you sound like Charlie Brown’s teacher.

- How long does it take to clip your bangs and brush your hair? Is she Marcia Brady?

- I didn’t realize going in that each segment runs about 30 minutes, so you can imagine my frustration as both segments prattled on long after I had lost interest. Surely, these reels will run out of film, right? I found the Ondine & Ingrid sequence particularly annoying, and was relieved when it finally ended.

Boys in Bed/Brigid Holds Court

- Things get slightly more interesting as Ed Hood and Rene Ricard lie in a presumed post-coital position in bed on the left, while Warhol favorite Brigid Berlin shoots up and makes phone calls on the right.

- If nothing else, “Boys in Bed” gives us some light bondage and male nudity courtesy of Rene Ricard. Apparently Ricard was one of the few actors in the movie who actually lived in the Hotel Chelsea at the time of filming.

- Brigid Berlin looks like a cross between Shelley Winters, Sandy Toksvig, and Large Marge. Yeah, that’s probably mean-spirited, but I have to take out my frustrations on this movie somehow.

- I suspect I would hate everyone in this movie. No, I will not elaborate.

Hanoi Hannah and Guests/Hanoi Hannah

- At this point in the film, I started pretending that each of these segments was happening in real time at different parts of the hotel, like an experimental episode of “24”. This theory was immediately squashed with the joint appearances of Hanoi Hannah (Mary Woronov). Both the left and the right segments involve Hannah in her room with fellow superstar International Velvet; smoking, talking, fighting, dictating fake bulletins to American soldiers in Vietnam. Ya know, girl stuff.

- I don’t know what the pecking order was among Warhol’s superstars, but Mary Woronov was clearly a favorite. Not only does she appear in at least four of these segments, she gets several extended close-ups as the camera stays tight on her face. I get it: with her stern eyebrows and striking features, Woronov always looks like she’s calculating or plotting, which is fun to project onto as an audience member.

- Of the actors in this movie, Mary Woronov would have the most prominent post-Warhol acting career, appearing in many a B picture and indie movie, most notably the 1982 black comedy “Eating Raoul”. She also shows up in an episode of “Faerie Tale Theatre”, which is where I know her from.

Marie Mencken [sic]/Mario Sings Two Songs

- After the film takes a breather with an organic halfway point, we are back up and running with filmmaker Marie Menken holding court on the left and a return for the Boys in Bed on the right.

- The Marie Menken episode is interesting because it’s the first of four segments filmed in color! And if the name Marie Menken sounds familiar, she is a fellow NFR filmmaker (see “Glimpse of the Garden”). My one question about her: Why is she so angry in this? Every time I look at the left side I see her yelling at someone in the room and brandishing a whip. Is this what life was like for her and her husband?

- The Boys in Bed get a visit from drag performer Mario Montez, who as promised sings two songs from the Irving Berlin musical “Annie Get Your Gun”: “They Say It’s Wonderful” and “I Got the Sun in the Morning”. As Montez finished the second number, I assumed that meant the segment would end. 20 minutes later my assumption turned into a desperate prayer.

Color Lights on Cast/Eric Says All

- It’s easy to understand how these two got paired together: they’re both color film of lighting tests conducted in, I presume, Andy Warhol’s studio. An assemblage of superstars make up the tests on the left while Eric Emerson gives a weird, extended monologue on the right.

- Most of the lighting involves the very patriotic combination of red, white, and blue. There are a few moments when all three colors are flashed in quick succession, making it look like the cops have pulled this film over.

- With his abundant hair and intense performance, mixed with the lighting effects, Eric looks like he’s about to start Willy Wonka’s “There’s no earthly way of knowing” monologue. What is this, a freakout?

- The sad thing is, before watching “Chelsea Girls”, I had a favorable opinion of Andy Warhol. I wish someone had convinced him to play all 12 of these at once so that I could get this over with in 30 minutes.

Nico Crying/Pope Ondine

- We end with the weirdest bookend ever. Nico and Ondine return, only now they’ve switched places: Nico on the left (and in color) quietly crying while light effects project on her face, and Ondine on the right giving an extended monologue about how he has become the new Pope.

- This combination was even worse the second time around, because this time I knew what to expect. Nico just stands there without saying anything, while Ondine rages on about whatever the hell he’s talking about. This led to me becoming increasingly hostile towards the movie as there seemed to be no end in sight.

- For the curious/masochistic, you can view the muted or partially muted sections of the film online: Nico in Kitchen, Brigid Holds Court, Hanoi Hannah and Guests, Hanoi Hannah, Marie Mencken, Mario Sings Two Songs, and Nico Crying.

- One final thing worth noting: As soon as this film ended (abruptly, with no credits), I did something I don’t think I’ve ever done while watching a movie for this blog: I booed. I booed this move loud and long and clear. I hated “Chelsea Girls” more than I can describe in 2000 words, but no matter what I write about it here, I know that I can never hurt it as much as it hurt me.

Legacy

- After a successful run at the Film-Makers’ Cinematheque in late 1966, “Chelsea Girls” became the first “underground” movie to play a wide release (though primarily through smaller arthouses across the country). Despite mixed critical reception and being banned in Boston and Chicago, “Chelsea Girls” was Andy Warhol’s first financial success as a filmmaker.

- “Chelsea Girls” helped propel the popularity of the Hotel Chelsea, as did the presence of one of the hotel’s most famous residents: Bob Dylan. The freeform lifestyle depicted in this movie came to an end in the 1970s following a series of negative incidents in the hotel, including the tragic murder of musician Nancy Spungen by her boyfriend Sid Vicious in 1978. Throughout the decades the Hotel Chelsea has changed owners, and in 2022 completed its conversion to a luxury hotel, mirroring the gentrification of the Chelsea neighborhood.

- I know I mentioned this in my “Empire” post, but it’s worth repeating: Andy Warhol made a guest appearance on a 1985 episode of “The Love Boat” where he reunites with a former Superstar played by Marion “Happy Days” Ross. God help me if “White Giraffe” ever makes the NFR.