#770) Chicana (1979)

OR “Days of Bread and Roses”

Directed by Sylvia Morales

Written by Anna Nieto-Gómez

Class of 2021

As of this writing, you can watch “Chicana” on the Internet Archive.

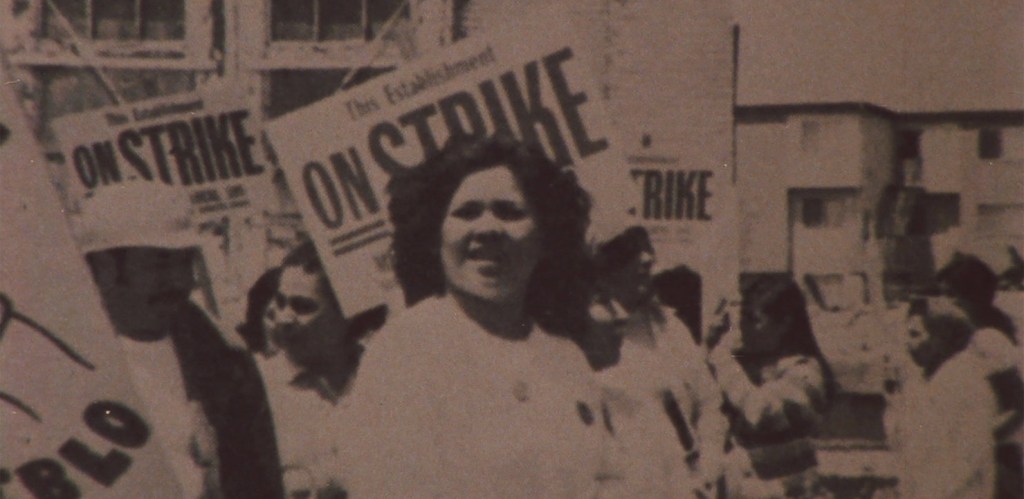

The Plot: As the first organized Chicana movement gives way to a new generation, Sylvia Morales takes a look back on centuries of Latinas and their struggles in “Chicana”. Narrated by actor Carmen Zapata, “Chicana” is a celebration and examination of Latina women throughout history. Among them: the Great Mother of pre-Aztec culture, La Malinche’s intermediary work with the Spanish conquistadors, Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez’s support for the Mexican War of Independence, Emma Tenayuca leading the 1938 San Antonio pecan shellers strike, and many many more. Through paintings and poems, sights and sounds, “Chicana” highlights the hardships, the successes, and the ongoing legacy of these important women, as well as the modern-era women who follow in their footsteps.

Why It Matters: The NFR’s lengthy write-up on “Chicana” calls the film “a brilliant and pioneering feminist Latina critique”, chronicling the film’s production and subsequent restoration at UCLA.

But Does It Really?: As an NFR entry, “Chicana” ticks off a lot of boxes: a documentary short about a historically marginalized group made by a person of color with a UCLA connection; that’s a bingo. On its own merits, “Chicana” is an engaging history lesson, shining a light on women I’m embarrassed to admit I knew nothing about. While there is a bit of homework that needs to be done to fully appreciate this film, it’s a worthwhile viewing experience worthy of its NFR status. Plus, anyone who can effectively streamline 2000 years of Chicana history into 22 minutes deserves all the recognition they can get.

Everybody Gets One: While studying film at UCLA, Sylvia Morales got a job as a camera operator at KABC, which parlayed into work producing a series of documentary specials for the station. Around the same time, Morales took a Chicano Studies course taught by Anna Nieto-Gómez, which included a historical slide show of Mexican women. Surprised by how many of these women she had never heard of, Morales started doing additional research on her own film about Mexican women which became “Chicana” (with narration written by Nieto-Gómez).

Seriously, Oscars?: No Oscar nod for “Chicana”, though Sylvia Morales would receive an Emmy nomination in the 1990s for the documentary series “A Century of Women”. For the record: the 1979 Oscar for Documentary Short Subject was won by a film that wouldn’t be too out of place in the NFR: Saul J. Turell’s “Paul Robeson: Tribute to an Artist”.

Other notes

- Our narrator is Carmen Zapata, one of those actors who never became a big-name star, but worked steadily in film, TV and theater for 50 years. Zapata also collaborated with a number of Hispanic actor organizations, including co-founding the Screen Actors Guild Ethnic Minority Committee. Even without seeing her, you can sense how seriously Zapata is taking her narrating duties, treating each subject with compassion and reverence. Currently, Ms. Zapata has one other NFR appearance: a brief cameo as the mother of the bride in “Boulevard Nights”.

- Shout out to Carmen Moreno, who composed the film’s score and plays the guitar throughout. Thanks to her upbeat score during the opening credits, I love this movie already, and we’re only two minutes in!

- “Chicana” begins with the “nurturing woman” stereotype that generations of Mexican women have been expected to follow. This explanation is spoken during a shot of a woman toilet-training a child, which tells you what this movie thinks of that patriarchal nonsense.

- My main takeaway from this movie was the dichotomy of how women are treated not just in Mexican culture, but across endless eras and societies. We simultaneously deify and condemn women for their mere existence. Heavy stuff, but it’s important to contemplate these big ideas, and I appreciate a film like “Chicana” for illustrating all this through a historical lens.

- This whole post could be me talking about the various research rabbit holes I went down learning about the women highlighted in the film. As you can imagine, “Chicana” can only touch upon each of its subjects for a few fleeting moments, but I encourage you to look up any of these women whose stories pique your interest. One that definitely got my attention was La Malinche, the Nahua woman who, in addition to her aforementioned work as intermediary to Hernán Cortés, was enslaved by the Spanish conquistadors and bore Cortés a son, one of the first Mesitzos. While this film paints La Malinche in a positive light, she’s a bit controversial in Mexican history, with the argument that she “betrayed” the indigenous people of Mexico. That is some thin ice we’re skating on, but pivotal in the history of Mexican culture.

- Catholics. Why is it always Catholics? The Spanish conquistadors of the 1500s brought Catholicism with them to the new world, and the religion continues to be a major factor in Mexican culture (according to their 2020 census, 78% of Mexico’s population identify as Catholic). Among the many unsung heroes depicted in this film is Juana Inés de la Cruz, a nun who wrote in the late 1600s advocating for women’s rights. Although this film implies that Sor Juana’s writings were burnt by a repressive church, that is most likely apocryphal.

- Since the film’s release almost 50 years ago, new information about many of these women have come to light. For example, labor organizer Lucia Gonzalez Parsons (aka Lucy Parsons) may not have been of Mexican descent. Information about her early years is spotty, and there are contradicting reports regarding her ethnic heritage (she was most likely African-American). Still, it’s nice to see her included in this historical line-up of important women.

- Another figure I found interesting was Valentina Ramirez, who disguised herself as a man to fight in the Mexican Revolution, with modern historians giving her the nickname “The Mexican Mulan”. And yes, the hot sauce is named after her.

- Our film ends by bringing us to the present (1979) with Morales’ brief interviews with activists Dolores Huerta, Alicia Escalante, and Francisca Flores, all of whom stress that the struggle and the fight for women’s rights continue. The film is bookended by a quote from poet James Oppenheim regarding the 1910s women’s suffrage movement: “Hearts starve as well as bodies, give us bread but give us roses.”

Legacy

- Sylvia Morales continues to write and direct for film and TV, has penned several books about filmmaking and Mexican history, and has taught film classes at USC. Morales’ most recent film is “A Crushing Love”, a sequel to “Chicana” focusing on the work-life balance of five Chicana activists (including Dolores Huerta and Alicia Escalante from this film).

One thought on “#770) Chicana (1979)”