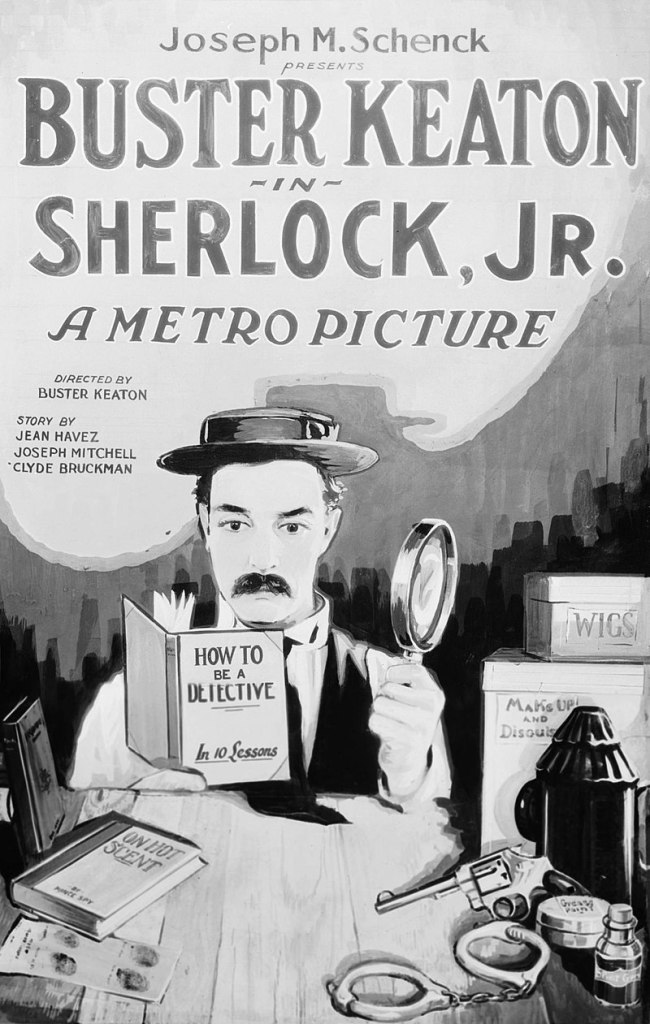

#59) Sherlock Jr. (1924)

OR “Hound of the Bustervilles”

Directed by Buster Keaton

Written by Jean Havez & Joseph A. Mitchell and Clyde Bruckman.

Class of 1991

This is a revised and expanded version of my original “Sherlock Jr.” post, which you can read here.

The Plot: Buster Keaton stars as a well-meaning, unnamed fellow working as a film projectionist at his local movie house. His attempts to woo his crush (Kathryn McGuire) are often thwarted by the town’s “local sheik” (Ward Crane), who goes as far as to frame Buster for the stolen watch of the girl’s father (Joe Keaton). While on the job, Buster falls asleep and dreams that he can enter the movie being played, in which he is transformed into the famous detective Sherlock Jr. His attempt to locate some missing pearls leads to the kind of inventive gag work that we now think of as classic Buster Keaton.

Why It Matters: The NFR calls the film no less than “a comedic masterpiece that both acknowledges and embraces the cinematic medium.”

But Does It Really?: Man oh man is this movie great. While “The General” is the best overall film in Keaton’s filmography, “Sherlock Jr.” is the most fun, and my personal favorite. With its flawless stunt work and downright magical special effects, there’s a point where even a movie buff like me stops trying to figure out how they did it and just sits back in awe of Keaton’s talents. And he delivers all of this in under 45 minutes! More movies should aspire to be as funny and concise as “Sherlock Jr.”; a perfectly constructed movie comedy and an absolute no-brainer for NFR inclusion.

Wow, That’s Dated: Mainly the profession of film projectionist. How is walking into your dream movie affected by film’s transition to digital?

Title Track: Keaton began work on this film under the title “The Misfit”, changing it to match his film-within-a-film character some time during previews.

Other notes

- Keaton already had two features under his belt by 1924: the previous year’s “Three Ages” and “Our Hospitality” (both of which I’m sure will make the NFR the next time the Preservation Board says “I dunno, how about another Keaton?”). The whole film was based around a single idea Keaton had of someone walking onto a movie screen and into the movie they were watching. Because of the intricacy of some of Keaton’s gag ideas, filming on “Sherlock Jr.” took four months, as opposed to Keaton’s usual two.

- One of the more interesting behind-the-scenes tidbits about “Sherlock Jr.” is who did or didn’t co-direct it. Depending on which source you believe; Roscoe Arbuckle – Keaton’s old boss who was still recovering from his scandalous rape/murder trial – was hired by Keaton to co-direct the film, but was quickly fired when he became difficult to work with, allegedly verbally abusing cast and crew. Arbuckle’s widow claimed that Arbuckle not only directed the whole movie, but even came up with the idea. This is greatly disputed, as is what – if any – of Arbuckle’s work made the final cut. Interesting to note that this is one of the few Buster Keaton movies in which he doesn’t have a credited co-director.

- The lost dollar bill gag is a good character moment. If you aren’t already endeared to Keaton as a performer, this scene will do the trick.

- I find it fascinating that even in 1924 Keaton felt the need to subvert the banana peel gag. Apparently this classic comedy bit has been around since the 1850s!

- That’s Buster’s real life dad Joe Keaton as the girl’s father, and you can definitely see the family resemblance. Joe Keaton was a vaudeville performer who started including his son in the family act when he was three. Although Buster’s childhood was marred by Joe’s alcoholism, by the 1920s their relationship had improved and Buster began casting him in supporting roles in his movies. Joe can also be spotted in Buster’s fellow NFR entries “The General” and “Steamboat Bill Jr.“.

- The “follow your man closely” sequence has some wonderfully funny physical bits, and is best known for Keaton’s most famous on-set injury. For those who don’t know the story: In the shot where Keaton jumps from a moving train, holds onto a water spout, and is pushed to the ground by the outpouring water, Keaton landed on the steel railroad track, though he recovered enough to continue filming the next day. Cut to nine years later when, during a routine x-ray exam, Keaton’s doctor noticed a callus in Keaton’s top vertebra. It turns out Keaton broke his neck when he landed on that railroad track, but his high tolerance for physical pain led him to essentially shrug it off and keep working! As with any Keaton stunt: Professional stunt person, do not attempt.

- Once Keaton enters the film-within-a-film, the real movie magic takes place. The jump cuts as Keaton is transported to a variety of locations is truly astonishing to watch. That being said, I guess this movie was a montage of establishing shots before Keaton showed up.

- I didn’t realize “Airplane!” stole the “walking through a mirror” gag from this movie. Now that I think about it, there’s a lot of stuff in the movie “Zero Hour” that also gets copied in “Airplane!” What kind of a two-bit operation is this?

- Sherlock Jr.’s assistant is named Gillette, a nod to William Gillette, the silent film actor best known at the time for playing Sherlock Holmes. Gillette is also described as “A Gem who was Ever-Ready in a bad scrape.” Har-de-har-har. Side note: With his seemingly endless supply of disguises and fake mustaches, Gillette is the Gene Parmesan of detective assistants.

- The bit where Buster disappears into the suitcase being held by Gillette in his peddler disguise is apparently an old vaudeville trick. This is twice now that I have looked up how exactly that stunt was pulled off, and I still don’t understand how it was done.

- The third act chase scene, which sees Buster on the handlebars of a runaway motorcycle, is perfect. Even up-to-now-ignored leading lady Kathryn McGuire gets to do a pratfall, as she topples into the backseat as a car takes off. Keaton recognizes that the real meat of the movie is the film-within-a-film, and once it reaches its conclusion, the real-world resolution is short and sweet.

Legacy

- “Sherlock Jr.” opened in April 1924 to mixed reviews and mediocre box office. Both critics and audiences felt the film was good, but not up to par with the likes of “Our Hospitality”. It wasn’t until Keaton’s filmography became reevaluated by a new generation of movie lovers in the early 1950s that “Sherlock” earned its reputation as one of Keaton’s best.

- The film-within-a-film elements of “Sherlock Jr.” has been recognized by film historians as one of the first bits of surrealism in film (though Keaton dismissed this designation in his lifetime). Among the film’s most obvious disciples are 1972’s “What’s Up, Doc?” with its riding-on-the-handlebars bike chase, and 1985’s “The Purple Rose of Cairo”, with its movie characters walking off the screen and into real life.

6 thoughts on “#59) Sherlock Jr. (1924)”