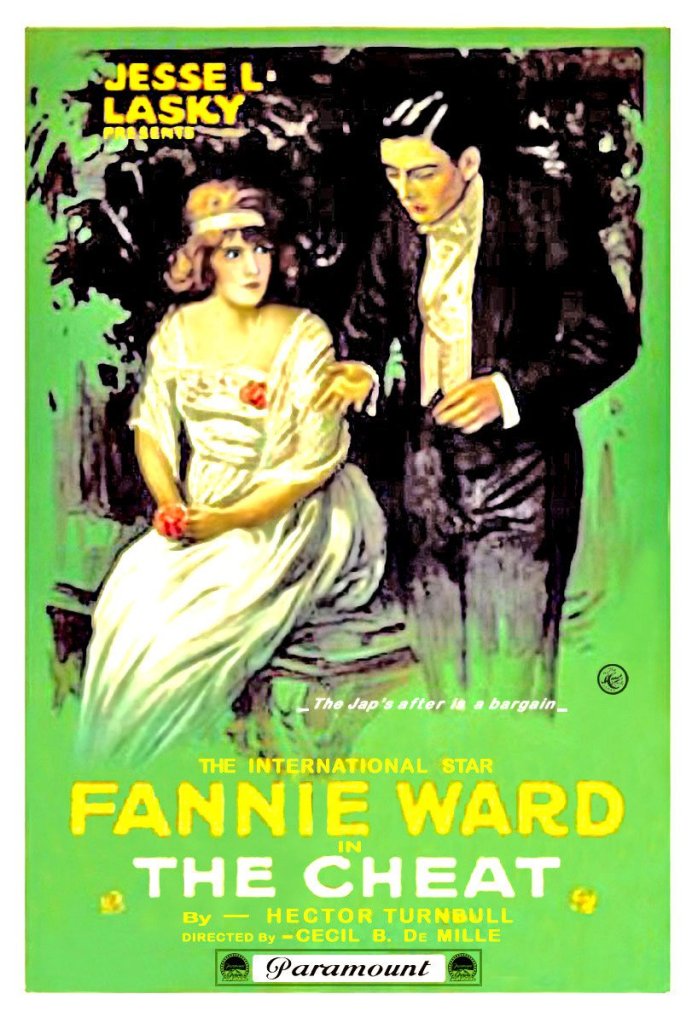

#673) The Cheat (1915)

OR “Your Money or Your Wife”

Directed by Cecil B. DeMille

Written by Hector Turnbull and Jeanie MacPherson

Class of 1993

NOTE: The only surviving version of “The Cheat” is a 1918 re-release of the movie. More on this version’s importance later on.

The Plot: Socialite Edith Hardy (Fannie Ward) loves spending money on her extravagant lifestyle, even though that money belongs to her husband Richard (Jack Dean), who can’t pay off her debts until his stock investment comes through. Acting on a hot tip from one of Richard’s colleagues, Edith places $10,000 raised by her local Red Cross chapter for Belgian refugees into a new stock that will double her money. The next day, Edith learns the tip was a fake and that all her money is lost. Horrified, Edith goes to Japanese Burmese ivory merchant Hishuru Tori Haka Arakau (Sessue Hayakawa) for help. Haka agrees to loan Edith the money, in exchange for a sexual dalliance the next day. What follows is a small melodrama about three people directed by the man who will one day bring us epic spectacles with a cast of thousands!

Why It Matters: The NFR says the film features “some of the silent era’s most potent plot twists and elaborate production design”. The write-up also praises Sessue Hayakawa’s “subtle yet menacing” performance.

But Does It Really?: I didn’t realize until researching this film how underrepresented Cecil B. DeMille is on the NFR; with only this and “The Ten Commandments” making the cut (plus his acting cameo in “Sunset Boulevard“). DeMille is such an important name in the history of American film that one of his early successes should be on the list, but “The Cheat” feels like an odd choice, especially considering how early into the NFR it made the cut. “The Cheat” is the kind of moralistic melodrama I’ve come to expect from the 1910s; hardly the kind of film I’d associate with Cecil B. DeMille, and certainly not my first choice to represent him. “The Cheat” is one of those NFR movies that seems to have skipped the line; it’s deserving of its NFR status for sure, but more as the kind of “I guess” choice the NFR would make in the 2010s after selecting all of DeMille’s essentials, and certainly not in the same class as “It Happened One Night” and “Godfather Part II“.

Everybody Gets One: By 1915, Fannie Ward had been a popular stage actress for many years, her perpetually youthful looks giving her an extended life as a leading lady. It was also around this time that Fannie married her second husband, fellow actor Jack Dean, and the two accepted an offer to come to Hollywood and make films with Lasky Players. “The Cheat” was the second film for both Fannie Ward and Jack Dean, and their earliest surviving film.

Wow, That’s Dated: Adjusted for inflation, the $10,000 dollars Edith owes would be over $300,000 today. Those poor Belgians.

Other notes

- First off, a little bit about Cecil B. DeMille. Born to a family of theater performers, DeMille started off as, naturally enough, a theater performer. Acting gave way to directing for the stage, and a screening of “Les Amours de la reine Elisabeth” in 1912 inspired a pivot to the new medium of film. Along with his theater colleagues Jesse L. Lasky and Samuel Goldwyn, DeMille cofounded the Jesse L. Lasky Feature Play Company, which would one day become known as Paramount Pictures. “The Cheat” was one of many films DeMille helmed in his first few years of making movies; it’s one of 13 films he made in 1915 alone! Fun Fact: The B in Cecil B. DeMille stands for Blount; his paternal grandmother’s maiden name (his maternal grandmother Cecilia was honored with his first name).

- Both Fannie Ward and Jack Dean are clearly stage actors. Their performances are playing to the back of the house, especially Dean, gesticulating like crazy and wearing a little too much makeup. On the other hand, you have Sessue Hayakawa being one handsome bastard who knows how to make love to the camera.

- This all being said, watching Sessue turn into a creep towards Fannie is very unpleasant. Damn you, Yellow Menace!

- One thing I noticed during this movie is that the dates are way off. All of the film’s events supposedly happen within the span of a few days, but Haka’s check is dated in June, Richard’s check is from September, and the newspaper headline before the trial is from April. I guess they really didn’t care about continuity back then. To be fair, nobody in 1915 thought that 108 years later some dude would be able to watch and analyze this movie on a screen in their home.

- So the moral of all this is don’t be impulsive? The closest this thing gets to a moral is an intertitle that quotes Rudyard Kipling: “East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.” Not only is that thoroughly disappointing, but now I got “Buttons and Bows” stuck in my head.

- A bit of foreshadowing to DeMille’s later spectacles is the third act courtroom scenes, which have a gallery packed with extras. And their ensuing lynch mob really showcases the kind of organized chaos that would become DeMille’s hallmark. There’s your cast of thousands.

- [Spoilers] Richard claims that he shot Haka when he takes the stand in order to protect Edith, who actually shot Haka. After he is found guilty, Edith hysterically confesses to the shooting, the judge dismisses the verdict, and Richard is set free. Now I’m no fancy city lawyer, but shouldn’t Richard at the very least be fined for perjury? Whatever, you can have your happy ending, Cecil.

Legacy

- “The Cheat” premiered in December 1915, and was an immediate hit with everyone – except for a large portion of the Japanese American community. Los Angeles based newspaper Rafu Shimpo objected to this film’s portrayal of its sole Japanese character as evil and manipulative, and waged a campaign against the film. When “The Cheat” was re-released in 1918, intertitles were re-written to make Japanese merchant Hishuru Tori into Burmese merchant Haka Arakau. Despite these changes, the film was banned in Japan and England, though did surprisingly well in France.

- “The Cheat” received three remakes: a 1923 version with Pola Negri (now unfortunately lost), a 1931 version with Tallullah Bankhead, and a 1937 French version with Sessue Hayakawa reprising his role from the original 22 years later!

- In 1921, French composer Camile Erlanger’s opera based on “The Cheat” – “La Fortaiture” – premiered in Paris (sadly, this was a posthumous premiere; Erlanger died in 1919). “La Fortaiture” is the first opera to be based on a film scenario, making “The Cheat” indirectly responsible for whatever movie turned musical is on Broadway right now. Let’s see, right now we’ve got “Aladdin”, “Lion King“, “Back to the Future“, “Some Like It Hot“, “Moulin Rouge!”…and coming up we’re getting “The Notebook” and “Days of Wine and Roses”. What a legacy.

- Neither Fannie Ward or Jack Dean’s film careers lasted too much longer after “The Cheat”, though they stayed married until Dean’s death in 1950. As for Sessue Hayakawa, he became the film’s breakout star, but an increasing typecast as a sexually dangerous heavy (along with rampant anti-Asian sentiment in Hollywood) led to his departure from American film, returning for such later classics as “The Bridge on the River Kwai” and “Swiss Family Robinson”.

- But of course, the biggest career boost from “The Cheat” was for Cecil B. DeMille, who spent the next 40 years producing bigger and bigger movies, culminating in his final, most famous movie: 1956’s “The Ten Commandments”.

Further Viewing: A selection of DeMille’s better known titles that have yet to make the Registry: “The Ten Commandments” (the 1923 version), “The King of Kings” (the 1927 version), “Cleopatra” (the 1934 Claudette Colbert version), “Samson and Delilah” (the 1949 version), and “The Greatest Show on Earth” (the…only version).

2 thoughts on “#673) The Cheat (1915)”