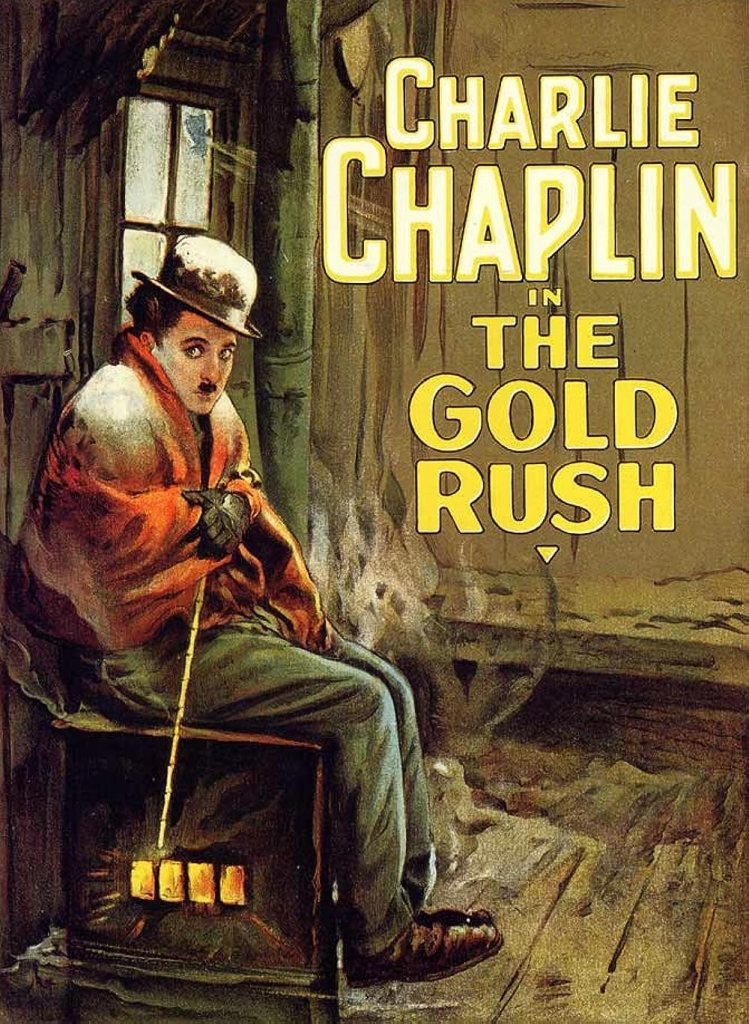

#4) The Gold Rush (1925)

OR “Yukon Do It!”

Directed and Written by Charles Chaplin

Class of 1992

Note: For this post, I watched the 1942 “revival” of “The Gold Rush”, the version most readily available when the film made the NFR. This is also a revised and expanded version of my original “Gold Rush” post, which you can read here.

The Plot: Charlie Chaplin reprises his popular role of the Tramp, who this time is The Lone Prospector traveling through the Yukon during the Klondike Gold Rush of the late 1890s. When a blizzard hits, the Tramp ends up trapped in a cabin with wanted criminal Black Larsen (Tom Murray), as well as Big Jim (Mack Swain), another prospector whose gold parcel has been buried by the blizzard. The three wait out the storm for several days, reaching a point of starvation and near-cannibalism. After the storm subsides, the Tramp journeys to a nearby boom town, falling for local dance hall girl Georgia (Georgia Hale). But as with so much of Chaplin’s work, all of this is just backdrop for his trademark mix of inventive comedy and heartfelt drama.

Why It Matters: The NFR states that the film is “[o]ften considered one of Chaplin’s greatest” and gives a rundown of the movie’s iconic scenes and Oscar stats. An essay by film historians Darren R. Reid and Brett Sanders delves into the influence Chaplin’s childhood of poverty had on his films and is a semi-promotion for their documentary “Looking for Charlie”.

But Does It Really?: I’ve watched “The Gold Rush” several times over the years, and as much as I enjoy it, it’s a movie that I admire more than I love. In only his fourth feature, Chaplin raises the stakes with massive sets and special effects, but still manages to keep the film character driven and packed with some decent laughs. “Gold Rush” is the first essential in Chaplin’s filmography, but his best work as an artist was still ahead of him. Still, you can’t have a list of iconic American movies without Chaplin eating his shoe and dancing with bread rolls, so “Gold Rush” is an absolute must for the Registry.

Everybody Gets One: Georgia Hale was cast in “The Gold Rush” after Chaplin saw her performance in Josef von Sternberg’s “The Salvation Hunters” and needed to re-cast his leading lady (more on that later). Chaplin would go on to hire Hale as a replacement for Virginia Cherrill as the Blind Girl in “City Lights” but ended up re-hiring Cherrill and discarding Hale’s footage (though some of it survives and has been released as supplemental material). Hale’s filmography spanned only seven years and 16 films, a majority of which are now lost.

Seriously, Oscars?: Well, here’s an interesting one: Originally released in 1925, “The Gold Rush” was obviously ineligible for the Academy’s first ceremony four years later, but the film’s 1942 re-release with a brand new soundtrack was nominated in two categories: Sound Recording, and Scoring of a Dramatic or Comedy Picture. Continuing Chaplin’s complicated relationship with the Oscars, “Gold Rush” lost in both categories to, respectively, “Yankee Doodle Dandy” and “Now, Voyager“.

Other notes

- In 1923, Chaplin’s first and only attempt at a straight-forward drama – “A Woman of Paris” – was not well received by his audience. Chaplin decided his next movie would be another comedy starring The Tramp, and inspiration for “The Gold Rush” came while he was reading about The Donner Party, the famous group of pioneers who got trapped in the Sierra Nevada and resorted to cannibalism for their survival. Not exactly “ha-ha” funny, but if anyone could successfully mine a dramatic scenario for humor, it was Chaplin.

- Production on “The Gold Rush” began in February 1924 in Truckee, California. Although initially planning to film entirely on location, two weeks into shooting Chaplin moved the entire production to his studios in Hollywood, building a massive recreation of the Klondike (the opening establishing shot of the miners heading into the mountains is the sole on-location shot in the final film). That September, production was halted when Chaplin learned that Lita Grey (his on-screen leading lady and real-life lover) was pregnant. When filming resumed in December, Grey had been replaced by Georgia Hale, who Chaplin would also have an affair with during production. Filming was completed in April 1925, with the film being released that summer.

- The 1942 version is dedicated to Alexander Woolcott “in appreciation of his praise of this picture.” I couldn’t find Woolcott’s specific review of “The Gold Rush”, but the New Yorker film critic and Algonquin Round Table mainstay was a big fan of Chaplin’s, calling his Tramp character “the finest gentleman of our time.” Woolcott died less than a year after “The Gold Rush” was re-released and dedicated to him.

- While I have admitted previously that I prefer Buster Keaton over Chaplin, that doesn’t make Charlie any slouch by comparison. While Keaton always had funnier gags, Chaplin made the better, more nuanced movies. Chaplin was such a talented filmmaker it’s easy to overlook the skill and discipline on display in his movies. His timing both on-camera and behind-the-scenes is flawless, and always imbued with character. There’s a point where superlatives don’t do him justice and you just sit back and admire the work.

- I get that this narration was recorded 17 years later, but Chaplin always sounds different that I think he will. So much more authoritative, so much more…British. I guess I’m thinking of what his Tramp persona sounds like in my head. Speaking of, I do love how Narrator Chaplin always refers to the Tramp as “the little fellow”. Very endearing.

- In addition to a few edits made by Chaplin, the 1942 re-release runs roughly 50% faster than the original 1925 version. That’s because film stock used during the silent era was projected at 16 frames per second (fps), while sound film has a projection rate of 24 fps. A silent film run through a sound projector is therefore going to have that sped-up quality we associate with the silent era.

- Iconic Moment 1 of 2: The shoe eating scene. Before the Donner party resorted to eating each other, they ate their own shoes to survive, and Chaplin took this detail and turned it into a meal (if you will). I love the detail of treating the laces like they’re strands of spaghetti. As best I can tell the shoe Chaplin eats was made of licorice.

- At one point Big Jim, out of starvation, starts to envision the Tramp as a giant chicken. Is this where we get the “hungry person sees someone as food” trope?

- I always forget how many live animals are in this: dogs, cats, a mule, a bear. Although once the bear enters the cabin it quickly switches from a real bear to a guy in a bear suit, which is still funny, and infinitely safer for everyone on set (except for maybe the guy sweating it out inside the bear suit).

- At a budget of $923,000 (roughly $16 million today), “Gold Rush” was one of the most expensive silent films ever made, and you can see that money on the screen. In addition to the Klondike set reconstructions and all those animals, “Gold Rush” has some genuinely impressive special effects, particularly the process shots and model work being done during the avalanche sequence.

- Georgia is…also a character in this movie. She doesn’t have much to do, but when the director has a crush on you, you’re going to look great. Fun Fact: The other actress considered to replace Lita Grey was a young unknown named Carole Lombard. She would have been great, but she also would have been 16, so 24-year-old Georgia Hale is a good call for everybody.

- The moments that made me laugh the hardest this viewing were any time sincere underscoring played during one of the Tramp’s pratfalls (getting knocked to the ground, getting pelted with a snowball, etc.) As always, ridiculous comedy is always funnier when played straight, and that goes for the music too.

- Iconic Moment 2 of 2: When the Tramp fantasizes about hosting Georgia and her friends for New Year’s Eve, he entertains them with the Oceana Roll dance, utilizing two bread rolls with forks stuck in them as his dancing legs. It’s a bit Chaplin used to do at parties that made its way into “The Gold Rush”/film immortality. The story goes that at the film’s Berlin premiere, this scene was so well received by the audience, the projectionist immediately replayed it for an encore. And who says Germans don’t have a sense of humor?

- While not as iconic as this movie’s other two big scenes, the cabin teetering over a cliff is another highlight. We get a surprisingly intense mixture of Chaplin’s flawless timing with more of those great special effects. The cherry on top for me is the Tramp thinking that the rocking cabin is just a side effect of his hangover, or in this movie’s parlance his “liver attack”.

- Wait, that’s it? The original version ended with the Tramp and Georgia sharing a romantic kiss, but by 1942 Chaplin’s affair with Georgia Hale was long over and he had the kiss removed, cutting abruptly from a shot of them walking away together to the end titles. Chaplin tries to smooth over the cut with narration, but it’s still a bit awkward.

Legacy

- Upon its release, “The Gold Rush” exceeded Chaplin’s expectations by being a critical and financial hit, ultimately becoming one of the highest-grossing silent movies of all time. Chaplin himself would often cite “Gold Rush” as the film he wanted to be best remembered for.

- Chaplin’s next film was 1928’s “The Circus”, which he made while simultaneously dealing with a divorce, the death of his mother, and trouble with the IRS. While not one of Chaplin’s more famous movies, “The Circus” earned him one of the first honorary Oscars at the inaugural Academy Awards.

- In 1942, Chaplin re-released “The Gold Rush” with a new soundtrack, new narration in lieu of title cards, and a few editing tweaks to tighten the pacing. This was the most readily available version of “The Gold Rush” until the early 1990s, when the 1925 version was restored. I’ve seen both and trust me, stick with the 1942 cut. The original is good, but longer and paced for a much more patient audience than me.

- In 1953, Chaplin did not renew the copyright on “The Gold Rush” (he was -ahem- out of town) and the film fell into public domain, leading to, as with so many other movies on this list, its frequent showings on TV and subsequent rediscovery by a new generation of film lovers.

- At the 1958 Brussels World Fair, “Gold Rush” was named the 2nd greatest movie ever made by a poll of over 100 film critics, falling just five votes behind Eisenstein’s “Battleship Potemkin”. Since then, “Gold Rush” routinely appears on various greatest films lists, including both AFI Top 100 lists.

- But of course, the film’s main legacy are the two iconic scenes mentioned above: the shoe-eating scene and the roll dance. The latter gets spoofed quite a bit, although at least one lawyer representing the estate of Charles Chaplin is quick to stop any “unauthorized imitation”.

Further Viewing: In 1979, Werner Herzog told aspiring filmmaker Errol Morris that if Morris ever finished making “Gates of Heaven”, he’d eat his shoe. Morris did, and Herzog’s end of the deal was documented in Les Blank’s aptly titled “Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe”. As expected, clips of Chaplin in “The Gold Rush” are featured.

10 thoughts on “#4) The Gold Rush (1925)”