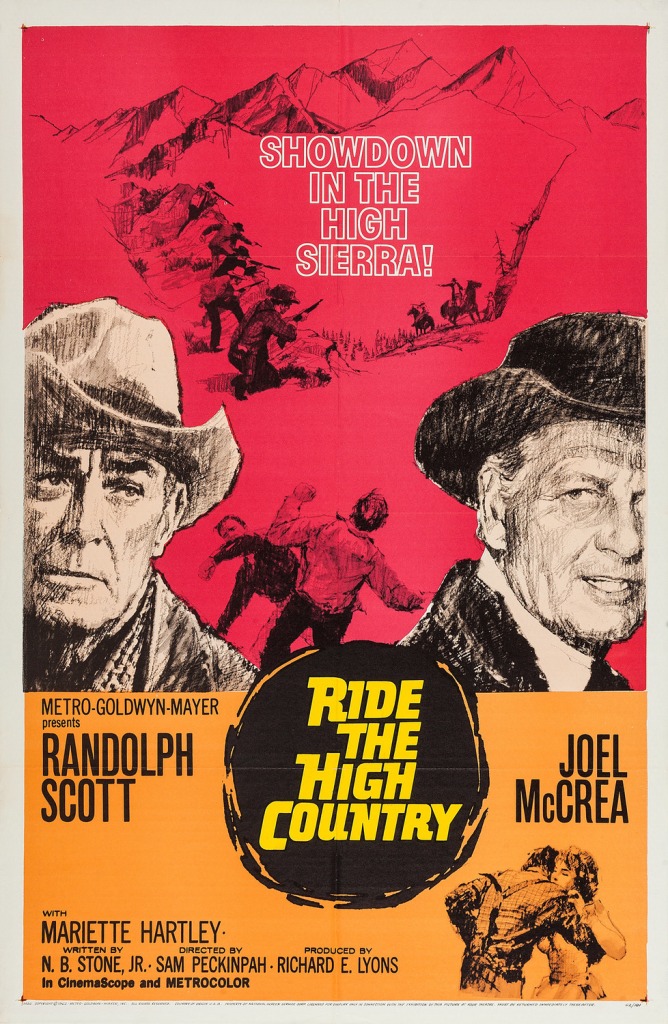

#692) Ride the High Country (1962)

OR “Grumpy Gold Men”

Directed by Sam Peckinpah

Written by N.B. Stone Jr. (with uncredited re-writes from Peckinpah and William Roberts)

Class of 1992

The Plot: At the turn-of-the-century in a much less wild west, aging lawman Steve Judd (Joel McCrea) is hired by a bank in Hornitos, California to transport gold from the mining camp Coarsegold in the Sierras (the high country, if you will). Aware of the trek’s potential hazards, Steve enlists the help of his former partner Gil Westrum (Randolph Scott), who in turn recruits his young assistant Heck Longtree (Ron Starr). What Steve doesn’t know is that Gil plans to double-cross him and take the gold for himself. En route, they meet Elsa Knudson (Mariette Hartley), who joins them on their travels to escape her oppressive father (R.G. Armstrong) and marry her fiancé Billy Hammond (James Drury), currently mining near Coarsegold. Once everyone arrives in Coarsegold, things do not go as expected in this rumination on morality in a changing world and only the second feature film from Sam Peckinpah.

Why It Matters: Unusually for an early NFR pick, there is no major superlatives in the film’s write-up. Instead we get a detailed plot synopsis, and reference to the film’s “poignant finale.” An essay by Peckinpah expert Stephen Prince is much more praising, highlighting the film’s uniqueness among Peckinpah’s later filmography.

But Does It Really?: I liked, but didn’t love, “Ride the High Country”. Admittedly my issues with the movie were my own genre bias, as well as a few other factors we’ll get to, but overall, it’s a well-made, character-driven western enhanced by a young director’s unique perspective. While I don’t object to the film’s NFR induction, I do question how it got on the list in only the fourth year. If you want Sam Peckinpah on the list, why not “The Wild Bunch”? If you want older actors revisiting their western days, why not “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance” or “Rio Bravo”? I’ll designate “Ride the High Country” as Peckinpah’s steppingstone film; the movie that was successful enough to get him the creative freedom that would lead to his better-known work. “Ride the High Country” is worthy of NFR preservation, but at the very least it should have switched places with “The Wild Bunch”, which had to wait another seven years before finally making the cut.

Everybody Gets One: Upon arriving in Los Angeles in 1927, Randolph Scott started out in the movies as a bit player and very quickly worked his way up to leading man status. Although he acted in a variety of genres, Scott’s domain was the Western: first in the 1930s in a series of movies based on the work of Zane Gray, and in the ’40s onwards as various lawmen trying to tame the west (I suspect this is the reason he is so revered in “Blazing Saddles“). Initially cast as the more law-abiding Steve Judd in “Ride the High Country”, Scott agreed to switch roles with Joel McCrea to play against type. Scott also successfully secured top billing over McCrea by winning a coin toss while the two were at lunch with Sam Peckinpah.

Title Track: N.B. Stone Jr.’s original screenplay went by the name “Guns in the Afternoon”. Among the numerous improvements Sam Peckinpah made in his re-write was the title “Ride the High Country”, an apt allegory for Steve’s morality. Composer George Bassman co-wrote a title song with lyricist Ken Darby that doesn’t appear in the film but was released as a single.

Seriously, Oscars?: No Oscar nominations for “Ride the High Country”, although the BAFTAs nominated Mariette Hartley for Most Promising Newcomer to Leading Film Roles. The only non-Brit in a category with Terrence Stamp and Sarah Miles, Hartley lost to Tom Courtenay for “The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner”. Home court advantage, I guess.

Other notes

- By the early 1960s, screenwriter N.B. Stone Jr. had fallen on hard times but had a screenplay he had written years earlier about two older men in the west that he wanted to see produced. His friend, fellow screenwriter William Roberts, gave the script to producer Richard Lyons, who declared it “awful” but liked its general concept. William Roberts did a full re-write but chose to remain uncredited out of respect for Stone (this is one of two westerns on the NFR that Roberts substantially re-wrote). Once Sam Peckinpah signed on as director, he exercised his contractual obligation for another re-write (a right he insisted on after losing creative control of his first film “The Deadly Companions”). Peckinpah spent four weeks re-writing most of the dialogue, infusing the character of Steve with many of the traits he admired from his own father, David. In addition, Peckinpah gave the film its new title, and made a major alteration to the film’s ending (more on that later).

- Admittedly, the timing of my “High Country” viewing didn’t help my overall enjoyment. I watched this shortly after watching “Bad Day at Black Rock“, another MGM-Cinemascope movie with aging movie stars demonstrating their sustained virility against a Sierra Nevada backdrop. While still very different movies, there’s enough shared DNA that gave “High Country” a feeling of sameness to “Bad Day”, which is no one’s fault by my own.

- In the 20 years since we last saw him in “Sullivan’s Travels“, Joel McCrea worked almost exclusively in Westerns, and was equally famous for turning down work to spend more time on his ranch (he considered himself a rancher who acted as a hobby). I’m glad McCrea signed on for “High Country”, because the straight-forward Steve fits him like a glove (though the idea of him initially playing Gil is intriguing; potentially a Henry Fonda “Once Upon a Time in the West“-style subversion).

- Even in his later years, McCrea continues to look like William Holden dubbed by Gary Cooper. He’s also still very tall, which is tough in a widescreen movie when he shares a shot with significantly shorter actors. Things improve when he’s paired with the equally tall Randolph Scott, and once they hit the Sierras everyone else can stand on a higher elevation level to match them.

- This is Mariette Hartley’s film debut (she even gets the “Introducing” credit in the opening). It’s a capable performance where she more than holds her own against her two established leads. And although Mariette Hartley’s film career never really took off, you can see her star quality that would make you believe that career path was possible. Elsa’s presence in the movie reminds me of McCrea’s great line in “Sullivan’s Travels”: “There’s always a girl in the picture. What’s the matter, don’t you go to the movies?”

- One line that made me laugh out loud comes from Gil, after watching Steve and Mr. Knudson tensely exchange Bible verses over dinner: “You cook a lovely ham hock, Ms. Knudson, just lovely. Appetite, Chapter One.”

- Ugh, I don’t need to see Joel McCrea or Randolph Scott in long johns! Make it stop!

- No offense to Ron Starr, who as of this writing is still with us, but he is not great in this. Starr’s acting career petered out within a decade of “High Country”, and hopefully he moved on to better things in another venue. Thankfully, his car navigation and safety systems seem to be much more effective.

- Another issue with this movie that is also my fault: I have no history with either McCrea or Scott. Aside from “Sullivan’s Travels”, I’ve never seen either of them in anything else, unlike someone my age in 1962, who would have watched their careers happen in real time and understand their history with westerns that’s baked into the film’s subtext. The closest thing I can equate this to is watching De Niro and Pacino all my life and then watching them revisit the gangster genre in “The Irishman”.

- Once everyone arrives in Coarsegold, I got massive flashbacks to my grade school field trip to Columbia, California, which is partially preserved in its gold rush aesthetic. Good times.

- Gah! Enough close-ups of the Hammond brothers! They’re all so off-putting. Side note: Henry Hammond is played by Warren Oates, aka GTO from “Two-Lane Blacktop“. If Henry is the kind of underdeveloped character Oates played in every Western, I see how the critics took notice of his work in “Two-Lane”.

- In one of my least favorite recurring themes on this blog, the whole Elsa & Billy wedding sequence is uncomfortable (though admittedly that’s the point). It leads to another round of unpleasant close-ups of the guests, particularly the Hammond brothers as they creepily leer at their new sister-in-law. All right cinematographer Lucien Ballard, you’ve lost your close-up privileges. Give me your keys.

- The last third of the movie takes its time, but we get some solid morality debates between Steve and Gil, the kind of gray area that started to crop up more and more in westerns. This all leads to the final showdown, which made me appropriately tense as I waited to see how it would all end.

- [Spoilers] In the original N.B. Stone draft, Gil was killed during the climactic shootout as an act of sacrificial redemption, but Peckinpah switched it so that Steve is killed, and Gil redeems himself by taking the gold to the bank. It’s a real downer of an ending, but also a surprising and more complex one. Even though I wasn’t fully engaged with the movie by then, I was genuinely saddened to see Joel McCrea slowly slink to the ground as the credits roll.

- I think the moral of this movie is don’t trust anyone under 50.

Legacy

- Although “Ride the High Country” tested well, MGM didn’t have faith in its box office potential and put it on the bottom half a double bill: first with the Italian swords-and-sandal epic “The Tartars”, and later with the sex comedy “Boys Night Out”. Reviews were mostly positive, with the film making it on a few year-end top ten lists (Newsweek even declared it the best film of 1962). This critical praise, aided by news that audiences preferred “High Country” over the top half of the bill, convinced MGM to re-release the film as a standalone feature in early 1963.

- After “Ride the High Country”, Randolph Scott felt he couldn’t top his performance and, after years of shrewd investments, retired from acting. Joel McCrea went back to his ranch after “High Country” but was occasionally talked out of his semi-retirement for a few more westerns before hanging it up for good in 1976.

- Although Mariette Hartley has a few more notable films on her resume (“Marnie”, “Marooned”, “Encino Man”), her best work was in television. Hartley has spent over six decades on various TV projects, including a run in the late ’70s/early ’80s where she got six Emmy nominations in five years (winning for a guest spot on “The Incredible Hulk”). And for the last time: No, she is not James Garner’s wife!

- Sam Peckinpah’s next film was 1965’s “Major Dundee” starring Charlton Heston, who hired Peckinpah based on his work in “High Country” (Side note: Heston also tried to remake “High Country” in the late ’80s starring him and Clint Eastwood, but nothing came of it). Although the production of “Dundee” was a disaster (not helped by Peckinpah’s chronic alcoholism), Peckinpah bounced back with his next and most famous film: “The Wild Bunch”.

One thought on “#692) Ride the High Country (1962)”