#776) George Stevens’ World War II Footage (1943-1946)

Filmed by George Stevens and the Special Coverage Unit

Class of 2008

“George Stevens’ World War II Footage” can be viewed on the Library of Congress website. For those of you who don’t have 6 1/2 hours to spare, I recommend 1994’s “George Stevens: D-Day to Berlin”, a 45 minute documentary by Stevens’ son George Stevens Jr. For those with even less time, Stevens Jr.’s other documentary about his dad, 1984’s “George Stevens: A Filmmaker’s Journey” contains about 10 minutes of the footage.

As always, this post is about the film, and not the war it is documenting. This write-up is a massive oversimplification of major WWII events, and I encourage you to do further research if any of this interests you.

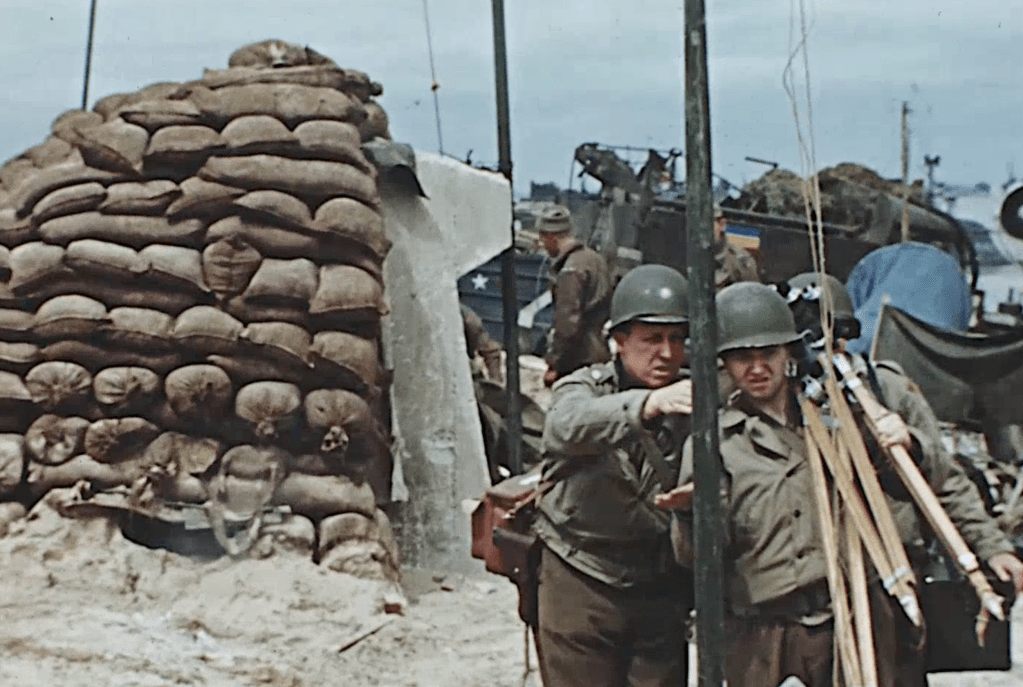

The Plot: Like many of his Hollywood contemporaries, director George Stevens contributed to the war effort by making films for the US military during World War II. In 1943, Stevens was ordered by General Dwight Eisenhower to recruit 45 people (primarily Hollywood cinematographers and screenwriters) for a Special Coverage Unit (SPECOU) to capture raw footage of the war. Armed with 16mm cameras and Kodachrome color film, Stevens and his team (nicknamed the “Hollywood Irregulars” or the “Stevens Irregulars”) captured over six hours’ worth of footage of the war as it was happening. Highlights of their documentation include the D-Day invasion in Normandy, the liberation of Paris, footage of the Dachau concentration camp a few days after its closure, and the streets of Berlin shortly after the end of the war. “George Stevens’ World War II Footage” is the most comprehensive color documentation of the war known to exist.

Why It Matters: The NFR gives the footage its proper historical context, and declares it “an essential visual record of World War II”.

But Does It Really?: Oh yeah. I am not a WWII expert by any means, but even I can appreciate the rare historic value of this footage. Most WWII footage I’ve seen is in grainy black-and-white, creating a distance between me and the footage, as if to say, “This all happened a long time ago.” But seeing the war in color makes the whole thing more immediate, more alive. It’s also refreshing after watching so much edited propaganda to see raw footage of the war without context or government-sanctioned narratives. This is as close as we’ll ever get to seeing the war as it actually was, and for that alone “George Stevens’ World War II Footage” is an indispensable addition to the NFR.

Other notes

- Before the war, George Stevens was an up-and-coming director with such hits as “Swing Time” and “Gunga Din” under his belt. Shortly after production wrapped on his comedy “The More the Merrier” in December 1942, Stevens attended a screening of “Triumph of the Will”, and upon seeing the film’s unflinching depiction of Hitler’s power was persuaded to join the war effort. In January 1943, Stevens enlisted with the US Army Signal Corps and was sworn in as a Major (by the end of the war he would achieve the rank of Lieutenant Colonel).

- Prior to his SPECOU assignment, Stevens spent the spring of 1943 in Africa, primarily Egypt and Algiers. His brief footage of Africa consists mainly of the sights (including the Sphinx and the pyramids) with some basic training and staged military action mixed in. Stevens transferred to Persia (now Iran) in June, and if he filmed any of his time there, it is not included in the Library of Congress’ online viewing collection.

- Once SPECOU had been assembled in early 1944, their first major assignment was to film the Normandy landings (aka the D-Day invasion) on June 6th, 1944. Stationed aboard the HMS Belfast, Stevens and his team documented the only known color footage of D-Day, primarily their voyage to and eventual arrival at Normandy. SPECOU also filmed black-and-white footage of the invasion, which was later edited into American newsreels covering D-Day. While nowhere near as frenetic as later reenactments in “Saving Private Ryan” and “The Longest Day”, seeing this footage of D-Day as it really happened is truly a sight to behold.

- Side note: There are many sources (including George Stevens Jr. in his documentaries) claiming that the Stevens WWII footage is the only color footage of the war in Europe. While color footage of the war is a rarity, let’s not forget William Wyler’s “The Memphis Belle”.

- On July 4th, 1944, SPECOU covered a ceremony awarding medals to survivors of D-Day attended by several high ranking officers, including Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, General Omar Bradley, and General George S. Patton! I don’t think I’ve ever seen the real Patton before, and I must say George C. Scott did his homework.

- Speaking of cameos and guys named George: George Stevens and his fellow filmmakers make several appearances throughout this footage. Stevens can be easily identified: He’s the tall one smoking a pipe and/or instructing the cameraman what to film.

- After D-Day, Stevens and his team joined up with the 2nd Armored Division headed by General Philipe Leclerc, en route to Paris following news of the city’s successful uprising against the Germans. Upon Leclerc’s arrival in Paris, Nazi Commander Dietrich von Choltitz surrendered to the French, ending Germany’s four year occupation of Paris. A large chunk of “George Stevens’ World War II Footage” is of the liberation of Paris on August 25th, a day Stevens later called “the greatest day of my life”. In addition to footage of Parisians celebrating in the streets, we witness General Charles De Gaulle’s return to Paris for the first time in four years, as well as sniper fire from the handful of Germans who refused to acknowledge the surrender. As far as the Allies were concerned, the Liberation of Paris was the beginning of the end, with SPECOU member Irwin Shaw betting Stevens the war would be over by October. But a surprise attack from the Nazis that December (the Battle of the Bulge), extended the war for the time being.

- Stuck in Germany in December 1944, Stevens filmed his unit celebrating Christmas, making this one of the last NFR titles I expected to add to my “Die Hard Not-Christmas” list. Of note is a shot of soldiers hanging grenades on their Christmas tree like ornaments, as well as a sequence of Stevens receiving a care package from his family, including letters and plenty of candy. This scene shows Stevens doing something we don’t see him do in any of the other footage: Smile.

- After a reassignment to London in early 1945 to help with the propaganda film “The True Glory”, Stevens returned to SPECOU in April to document the meeting of US and Soviet soldiers on the Elb river near Torgau. It’s an enjoyable bit of levity in the midst of all this darkness, but it’s still weird to see Americans and Russians getting along. Enjoy it while it lasts, boys.

- As with any war footage, there are plenty of unsettling images in this collection, including violent attacks and abandoned corpses. Unsurprisingly, the most disturbing, sobering section of this footage is the unit’s documentation of the Dachau concentration camp in late April 1945, mere days after its liberation. As with the rest of the footage, seeing Dachau in color makes the tragedy all the more real, with shots chronicling piles of corpses and the few gaunt survivors, as well as the bodies of Nazi soldiers who had been beaten to death by the inmates following the liberation. Stevens later recalled that the sights at Dachau made him realize the potential of evil hiding inside all of us; that anyone under the right circumstances is capable of the inhumanities the Nazis perpetrated. Stevens spent the rest of 1945 in Germany compiling concentration camp footage to be used as evidence in the Nuremberg trials.

- Shortly after the surrender of Germany on May 8th 1945 (V-E Day), Stevens and his team reached Berlin. Their footage of Berlin in the immediate aftermath of the war is fascinating. When I think of the end of WWII, I think of big celebrations, of sailors coming home and kissing random women. What this footage showed me was the aftermath of a city that had actually been in battle: streets covered in debris and a city divided into allied occupation, and the seeds of what will one day become the Cold War. The Stevens footage ends with the realization that even when war is over, it’s never over.

Legacy

- George Stevens returned to Hollywood in March 1946, stating that “Films were much less important to me, and in a way, perhaps, more important”. Not counting a segment of the anthology film “On Our Merry Way”, Steven’s first post-war film was 1948’s “I Remember Mama”, which took place in 1910s San Francisco, the time and place of Stevens’ childhood.

- Steven’s post-war filmography was devoid of the kind of light comedies and adventure pictures he was known for in the 1930s, opting instead for serious fare that examined human ideals. His next three films after “Mama” have all been inducted into the NFR: “A Place in the Sun”, “Shane”, and “Giant”. Among the names found in the credits of these films are screenwriter Ivan Moffat and cinematographer William Mellor, two of the many men who served with Stevens in SPECOU.

- Stevens’ only post-war film that dealt directly with the war was 1959’s “The Diary of Anne Frank”. While other war films were considered, Stevens found himself most drawn to “Diary”, especially once he learned that at one point during the war he and his unit were only 100 miles away from the attic in Amsterdam where Frank and her family were hiding.

- Following Stevens’ death in 1975, his son George Jr. oversaw the restoration of his father’s WWII footage at the American Film Institute. Stevens Jr. would later use this footage in the two documentaries I mentioned at the top of this post.

- Here’s a recent, weird coda to the “George Stevens: D-Day to Berlin” documentary. It turns out that the film was an edited version of a 1985 special produced for the BBC similarly titled “D-Day to Berlin” by Paul Woolwich and Robert Harris. In 2019, Woolwich and Harris learned of the 1994 “D-Day to Berlin” and sent a request to the Television Academy to launch an investigation of how closely Stevens’ film copied theirs. The Television Academy determined that Steven’s version was indeed a slightly altered version of the BBC documentary, and made the rare decision to rescind the three Emmys and four nominations Stevens’ version received in 1994. (Stevens has never commented publicly about the Academy’s decision).

Further Viewing: I have somehow covered this much NFR wartime propaganda without mentioning “Five Came Back”. Based on the book by Mark Harris, “Five Came Back” is a three-part documentary by Laurent Bouzerau about five Hollywood filmmakers — Frank Capra, John Ford, John Huston, George Stevens, and William Wyler — and their experiences on the front lines making films for the war effort, and how those experiences effected their films after the war. Of the five, John Ford is the only one who doesn’t have at least one of his wartime films on the NFR, which means I should mentally prep myself now for the inevitable inclusion of “The Battle of Midway” or “December 7th“.