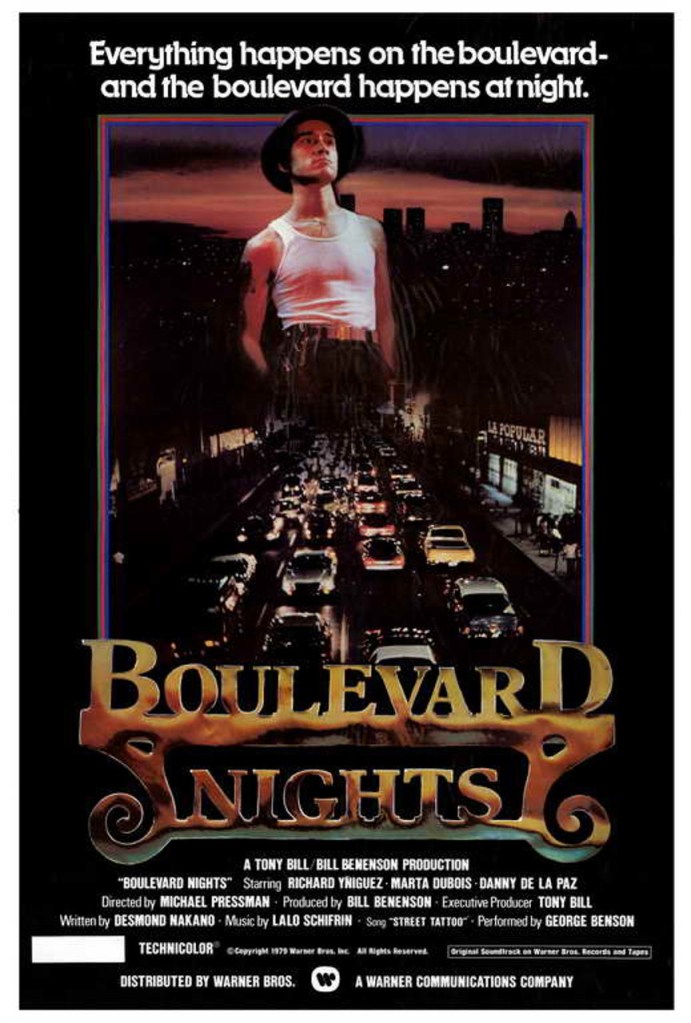

#721) Boulevard Nights (1979)

OR “Easy Lowrider”

Directed by Michael Pressman

Written by Desmond Nakano

Class of 2017

The Plot: “Boulevard Nights” centers on two brothers in East L.A.’s Mexican community; older brother Raymond (Richard Yniguez) loves driving his souped-up Chevrolet on Whittier Boulevard and going out with his girlfriend Shady (Marta DuBois), while younger brother Chuco (Danny De La Paz) is a member of the local street gang VGV, which is embroiled in a rivalry with the 11th Street gang. As a former member of VGV, Raymond tries to persuade Chuco to see his potential outside of the gang, getting him a part-time job at a local auto shop. As Raymond and Shady prepare to get married, Chuco’s devotion to VGV gets him into further trouble as their beef with 11th Street escalates into a full-out turf war. And if none of that interests you, this movie offers a whole bunch of great ’70s cars to feast your eyes on.

Why It Matters: The NFR calls the film “a pioneering snapshot of East L.A.”, and contextualizes the film with the other “gang” films of the era: “The Warriors”, “The Outsiders”, etc.

But Does It Really?: In all honesty I couldn’t get into “Boulevard Nights” and was ready to write it off as an anomaly on the NFR. But shortly after I finished this post, something remarkable happened to this movie: It got a Blu-ray release. Suddenly a number of articles popped up about this film’s significance as documentation of 1970s East L.A., and I had to rethink this whole post. As a standalone movie, “Boulevard Nights” is okay, but you’ve seen better versions of this same story in 100 other movies. Prior to its very recent reevaluation, most write-ups about this film’s importance could only connect it to “The Warriors” and the countless other gang films of the late ’70s. And if that’s all this movie had going for it, why not just induct “The Warriors”, which is much better remembered today and as of this writing still isn’t on the NFR? Fortunately, the support from this film’s Blu-ray release made me see the love a small but spirited group of L.A. cinephiles have for this movie, so “Boulevard Nights” gets a pass for its NFR induction. I’m happy for the people who champion this movie, but I’m ready to move on.

Everybody Gets One: Both this film’s director and screenwriter were the children of showbiz fathers: Michael Pressman’s father David was a blacklisted director, and Desmond Nakano’s father Lane was an actor. Desmond wrote the screenplay for “Boulevard Nights” while studying at UCLA, and it won the school’s Samuel Goldwyn Writing Award. This got the attention of producer Tony Bill, who optioned the script and financed the film independently with Warner Bros. serving as distributor. Pressman seized the opportunity to direct “Boulevard Nights” to prevent being pigeonholed as a comedy director (he had previously helmed “The Great Texas Dynamite Chase” and “The Bad News Bears in Breaking Training”).

Wow, That’s Dated: This whole thing is very late ’70s but look no further than Raymond’s feathery hair. It’s beautiful, but it dates everything.

Title Track: It tickles me that this movie has a theme song. I have no idea what Warner Bros.’ marketing strategy was, but we got “Street Tattoo (Theme from ‘Boulevard Nights’)” as a result. The song is performed during the end credits by George Benson, with music by Lalo Schifrin, lyrics by Gale Garnett, and additional special lyrics written and performed by Greg Prestopino.

Other notes

- “Boulevard Nights” was notably filmed entirely on location in Los Angeles. Despite concerns that filming in East L.A. would be dangerous, production went smoothly, in part because the filmmakers insisted on collaborating with the community, employing many residents both in front of and behind the camera.

- I feel like this movie starts on the wrong foot. Throughout the opening credits, we follow two 11th Street gang members as they walk through East L.A. early in the morning. As one of them is spray-painting the 11th Street insignia over a VGV tag, the VGV show up and start beating him. This only stops when Raymond appears, and the young 11th Street members run off. This was all set up in a way that made me think the 11th Street gang was our protagonists, and the next scene of Raymond and Chuco getting ready for work prompted me to say out loud “Wait, he’s the main guy?”. The whole opening is being told from the wrong perspective, taking me a little bit longer to get used to this movie. Speaking of the opening credits: Is that the “Welcome Back, Kotter” font?

- Once I adjusted to Raymond being the protagonist, the film follows him on an exciting Saturday night cruising on Whittier Boulevard. This got me on board with the idea that “Boulevard Nights” is a “Saturday Night Fever” / “American Graffiti” kind of thing; young people hanging out and coming of age. But then they really veer into the gang movie tropes and I guess this is the movie now.

- No disrespect to this cast, many of them making their film debuts, but they are across the board not great. No one’s terrible, but no one stands out as being particularly good. But in everyone’s defense, the screenplay is of no help in that department, with too many cliches and tropes working against any authentic performances.

- The only actor I recognized from this cast is Carmen Filpi, who plays Mr. Diaz the local tattoo artist. I know Filpi best as Jack, the hobo that rides the rails with Pee-Wee in “Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure”.

- I’m always happy to hear a Lalo Schifrin score (his “Cool Hand Luke” theme is one of my favorites), but what’s with the sad “Incredible Hulk” music as Chuco walks the streets by himself? (And for the record “The Lonely Man” was composed by Joe Harnell)

- [Spoilers] The plotline of Raymond and Shady getting married goes smoothly; so smoothly in fact that I became increasingly suspicious that something terrible was going to happen to these two. Raymond and Shady go through with the wedding as planned, but during the reception an 11th Street gang member, aiming for Chuco, shoots Mrs. Avila (Raymond and Chuco’s mother) instead. Having recently gotten married myself (humble brag), I’m glad I didn’t see this movie before my own wedding. Granted, I currently have no beef with any local gangs that would prompt such a tragic occurrence, but you know me, I’ll worry about anything.

- I really don’t have a lot to say about this movie. It was fine, but its NFR standing is more historical than artistic. In an effort to end on a positive note, I will say that I liked the car stuff with the hydraulics. That was cool. Why couldn’t the movie be more about that?

Legacy

- “Boulevard Nights” was released in March 1979, just a few weeks after “The Warriors”, and was met with similar protests from people who were worried the film would incite riots and gang activity in the theaters. Despite Warner Bros.’ attempts to downplay the film’s gang elements, there were a handful of fatal shootings and stabbings upon the film’s release, prompting San Francisco to pull the film entirely. Despite these setbacks (and a mixed-to-negative critical response), “Boulevard Nights” managed to make a small profit in theaters. Since then, the film has attained what the NFR calls a “semi-cult status”, with the likes of Quentin Tarantino championing the film’s detailed presentation of East L.A.

- Desmond Nakano would go on to write the film adaptation of “Last Exit to Brooklyn”. He also wrote and directed two feature films: 1995’s “White Man’s Burden” and 2007’s “American Pastime”, the latter based on his father’s experience in a Japanese internment camp during WWII.

- Michael Pressman’s directing career continues to this day, primarily in television, directing episodes of everything from “Picket Fences” to “Weeds” to “Blue Bloods”. And because I had to put this somewhere: In 1991 Michael Pressman directed – and this is true – “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II: The Secret of the Ooze”. Cowabunga indeed.