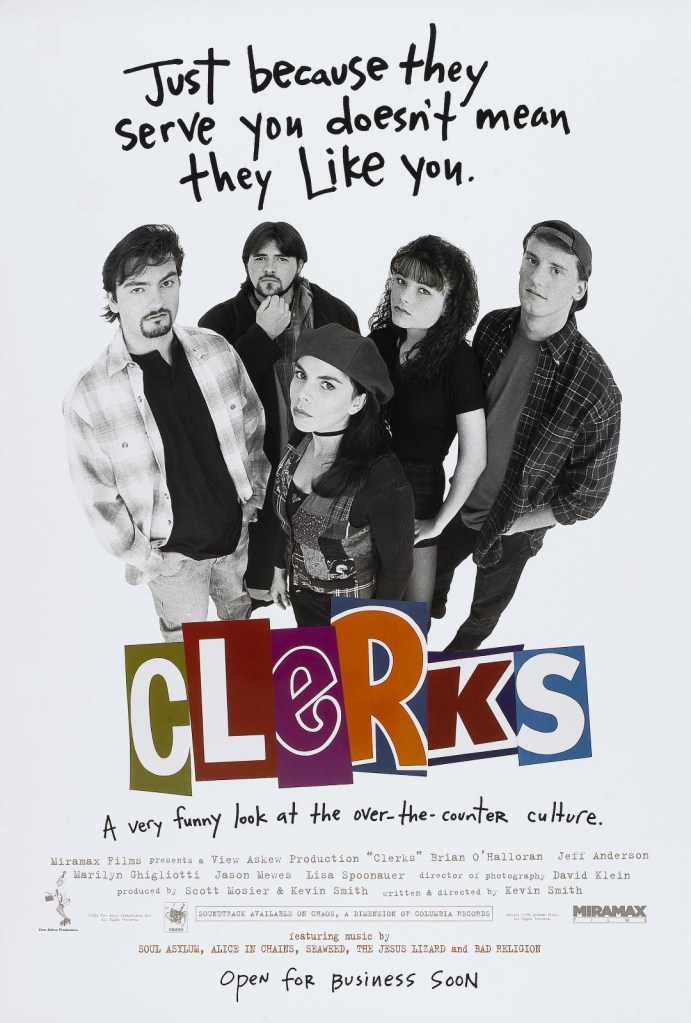

#780) Clerks (1994)

OR “Shift Happens”

Directed & Written by Kevin Smith

Class of 2019

The Plot: Dante Hicks (Brian O’Halloran) is called in on his day off to cover a shift at the Quick Stop Groceries convenience store in Leonardo, New Jersey. The day proceeds normally, with Dante receiving visits from his girlfriend Veronica Loughran (Marilyn Ghigliotti), and his best friend Randal Graves (Jeff Anderson) who works at RST Video next door. But as the day wears on, Dante’s luck gets increasingly worse: interacting with a number of bizarre customers, receiving the news that his ex-girlfriend Caitlin Bree (Lisa Spoonauer) is engaged, and trying to ward off Jay and Silent Bob (Jason Mewes and Kevin Smith) who are not-so-discreetly conducting their drug dealing business in front of the Quick Stop. And from these humble beginnings comes the crass, clever, pop-culture infused, jersey-clad work of Kevin Smith.

Why It Matters: The NFR calls the film “hilarious, in-your-face, [and] bawdy-yet-provocative”. The rest of the write-up is a rundown of Kevin Smith, as well as a lengthy blurb from Roger Ebert’s review of the film.

But Does It Really?: As I said the day the Class of 2019 was announced: “Oh for the love of— who put Kevin Smith on the list?”. At first glance, “Clerks” is an odd choice for the National Film Registry, but upon further inspection, its inclusion checks off a lot of boxes. Like many other NFR entries, “Clerks” is an era-defining hit that put its filmmaker on the map, and spawned a franchise and cult following that continues decades after the original film. On its own, “Clerks” is crude (in every sense of the word), but makes up for its guerrilla filmmaking aesthetic with sharp dialogue that captures the existential banality of working customer service. While I’ve never had anything for or against Kevin Smith, this viewing of “Clerks” made me appreciate his place in our movie landscape, and while I have mixed feelings about the final film, I have no objections to “Clerks” making the NFR cut.

Shout Outs: The most iconic scene in the movie comes from Dante and Randal’s conversation about “Return of the Jedi” (with Dante calling “Empire Strikes Back” the superior film). We also get a “Jaws” parody and, thanks to several shots inside the video store, at least 21 other NFR movies available to rent on VHS, from “2001: A Space Odyssey” to “A League of Their Own”.

Everybody Gets One: Hailing from Red Bank, New Jersey, Kevin Smith was inspired to become a filmmaker after seeing Richard Linklater’s “Slacker”, which made Smith realize he could make a movie locally without dealing with Hollywood studios. Smith attended Vancouver Film School for four months before dropping out and starting production on his own movie based on his experience working at Quick Stop Groceries in Leonardo, an unincorporated community near Red Bank. Oh, and like his main characters, Smith was 22 years old when he made “Clerks”. Take that, Orson Welles!

Wow, That’s Dated: Mainly the fact that Randal works at a video rental store. If I were Randal I wouldn’t be so smug when a customer vows never to return.

Seriously, Oscars?: No Oscar nods for “Clerks”, but it did receive three Independent Spirit nominations, including Best First Feature and Best First Screenplay. “Clerks” lost both of these awards to David O. Russell’s “Spanking the Monkey”, a title that somehow isn’t one of the adult movies Randal lists off.

Other notes

- The production of “Clerks” is well-documented, but a few items are worth repeating here. “Clerks” was filmed in the spring of 1993 on a budget of $27,575 (about $60,000 today). Smith obtained this budget by – among other things – working at the Quick Stop, selling his comic book collection, borrowing money from his parents, and maxing out multiple credit cards. After “Clerks” was a hit, Smith was able to buy back his comic book collection (and I assume pay off those cards and repay his parents). “Clerks” was shot in 21 days on black-and-white film stock, with many scenes covered in a single take. Several of these one-take scenes feature the actors saying their dialogue quickly, no doubt an effort to save both time and film.

- The Quick Stop and RST Video featured in “Clerks” are the actual stores that Kevin Smith worked at while making the film. Smith was only allowed to film inside the Quick Stop at night after hours, so an in-universe explanation as to why the store’s window shutters are closed throughout the movie was added to the screenplay. It’s simple, but it works.

- Right out the gate, this movie is unsettling me. That has got to be the weirdest, most off-putting production credits logo ever. And that’s just the Miramax logo. Thank you and goodnight!

- Unsurprisingly, most of the cast are local actors and/or friends of Kevin Smith. Brian O’Halloran auditioned for the movie after seeing an audition notice in his community theater, and while his work as Dante isn’t the greatest leading man performance ever committed to celluloid, he holds the movie together, which is all you can ask for in a movie protagonist. Side note: Was that goatee ever in style?

- This movie is so aggressively ‘90s. There’s something about disenchanted young Gen-Xers rattling off pop culture references that encapsulates this era of filmmaking so succinctly. Between this and “Pulp Fiction” (also released by Miramax around the same time as “Clerks”), its feels like independent filmmaking finally found its voice in 1994.

- This is your reminder that there is now a movie on the NFR in which “snowballing” is discussed. If you haven’t seen this movie, please don’t Google that.

- I’m so used to seeing Jay and Silent Bob in bigger movies (and in color) that it’s weird to see them here as supporting characters in a low-budget black-and-white movie. On a related note, Kevin Smith has somehow not aged in 30 years.

- Even at 22, Kevin Smith knew how to make a movie. It’s all rudimentary, but like many an independent filmmaker, you can sense Smith’s love of the game. In addition to writing, directing, producing, and acting, Smith co-edited the film with co-producer Scott Mosier. Given the confident rhythm of the editing, you get the sense that the film wasn’t saved in the edit, but rather enhanced by it, particularly the well-timed cuts that take us from one vignette to the next.

- Multiple actors pull double-duty in this film, but shoutout to Walt Flanagan who shows up as four different minor characters throughout the movie. Flanagan kept getting parts when their original actors flaked on production, and I didn’t realize all four characters were played by the same actor until Flanagan’s name kept popping up in the end credits.

- Despite my issues with “Clerks”, I must admit I laughed out loud quite a bit during my viewing. My favorite line in the movie is Randal declaring, “This job would be great if it wasn’t for the fucking customers”. I’ve said very similar things throughout my own customer service experience. Other lines I found funny include Dante’s refrain of “I’m not supposed to be here today,” and the running gag about the store smelling like shoe polish.

- Of all of this movie’s low-budget hacks, my favorite is the sweater that Rick the trainer is wearing that completely covers his arms. Just take our word for it: He’s ripped.

- Speaking of low-budget filmmaking: How do you stage a fight in a real convenience store without damaging any property? The answer: Not well.

- The film’s ending feels abrupt, but there’s a reason for that. As Dante is closing Quick Stop for the night, he was originally going to be shot and killed by someone robbing the store. Kevin Smith based this sudden downer of an ending on the final scenes from “Do the Right Thing”, though he admitted later that he wrote it because he “didn’t know how to end a film.” It was definitely the right call to cut this: As much as I was let down by the film’s anticlimactic ending, I would rather be confused by its suddenness than depressed by its tragic tonal shift.

Legacy

- “Clerks” was first screened at the 1993 Independent Feature Film Market…to an empty theater. Despite this less-than-stellar start, “Clerks” had support from producers Robert Hawk and John Pierson, who convinced Smith to cut the original ending. “Clerks” played the 1994 Sundance Film Festival, where it was purchased by Miramax and given an additional $230,000 for post-production and music clearances. After initially receiving an NC-17 rating for its coarse language (and getting bumped down to an R with zero cuts made) “Clerks” was released in October 1994 in two theaters, and over the next six weeks played in 82 additional theaters, earned three million dollars at the box office, and quickly amassed a cult following.

- Kevin Smith co-founded View Askew Productions to make “Clerks”, which continues to be his production company to this day. Smith quickly followed up “Clerks” with 1995’s “Mallrats”, which features a return from Jay and Silent Bob, making “Mallrats” the first connective tissue in the View Askewniverse. As of this writing, there are eight films in the View Asknewniverse, including “Dogma”, “Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back”, and the two direct sequels to “Clerks”. I wasn’t expecting “Clerks” to be the “Iron Man” of an extended cinematic universe, though given Smith’s love for comic books, I shouldn’t be surprised by it.

- There have been two attempts at a “Clerks” TV series. A pilot was developed in 1995 by Touchstone Television without Kevin Smith’s involvement, but was deemed awful by all involved and never picked up. Smith was directly involved with “Clerks: The Animated Series”, which was quickly canceled by ABC in 2000 after airing only two of the six produced episodes.

- The Quick Stop seen in “Clerks” in still standing, and has definitely leaned into its status as a famous filming location. The RST Video next door, unsurprisingly, closed decades ago, and is currently being used for storage. Attempts to reopen RST Video around 2019 seem to have fallen by the wayside.

- And finally: “Clerks” is one of the rare NFR movies to inspire another movie about its production.“Shooting Clerks” was written and directed by Christopher Downie, who would go on to lead the grassroots Twitter campaign that eventually got “Clerks” into the Registry, with the NFR announcing that “Clerks” received the most public nominations in 2019. Well movie geeks, your voice was heard. Happy now?