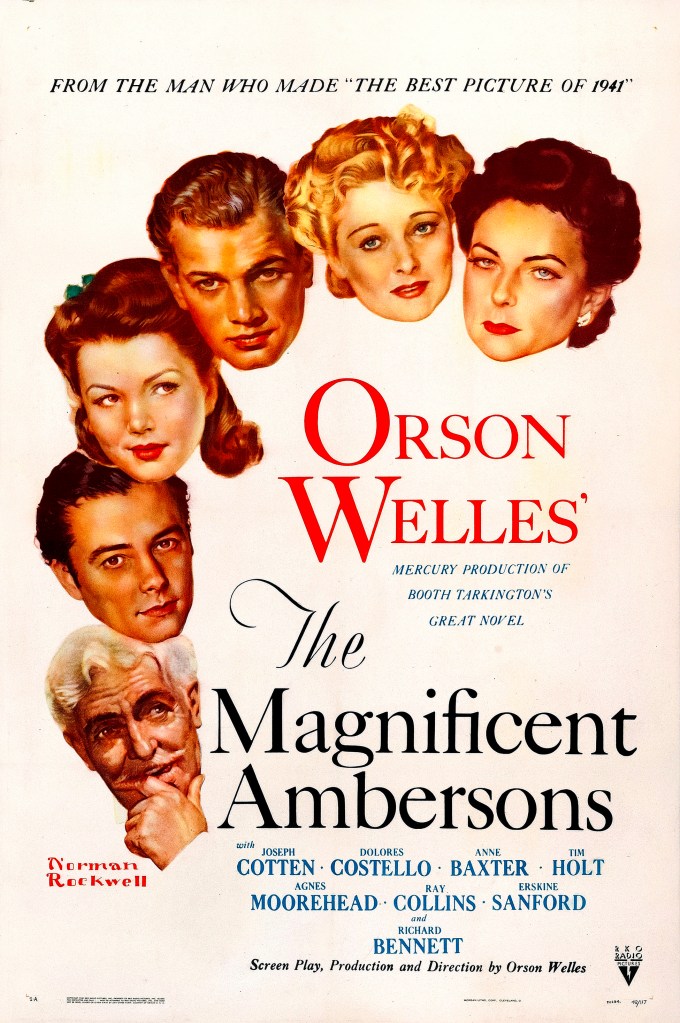

#669) The Magnificent Ambersons (1942)

OR “Furious George”

Directed and Written by Orson Welles. Based on the novel by Booth Tarkington.

Class of 1991

The Plot: In a Midwestern town around the turn of the century, the Ambersons are the wealthiest family with the most expensive mansion. In her youth, Isabel Amberson (Dolores Costello) was courted by Eugene Morgan (Joseph Cotten), but she rejected his advances and married Wilbur Minafer (Don Dillaway). Stuck in a loveless marriage, Isabel chose to spoil their son George (Tim Holt!), who grew up to be an arrogant mama’s boy. 20 years later, Eugene returns to town with his daughter Lucy (Anne Baxter), who George takes a liking to, unaware of their parents’ past. Eugene is now a successful automobile manufacturer, and George becomes increasingly agitated by Eugene’s attempts to rekindle things with Isabel. It’s a multi-generational family drama with meditations of how future technology corrupts past innocence, brought to nuanced life by the director of “Citizen Kane“, and completely botched by RKO’s subsequent tampering.

Why It Matters: The NFR write-up calls the film Welles’ “most personal and most impressive”, hailing the “stylish mastery” of the creative team and states that the ensemble includes “some of the best acting…to be found in American movies.”

But Does It Really?: Something had to follow “Citizen Kane”, which I guess makes “The Magnificent Ambersons” the greatest sophomore slump in movie history. Like “Kane”, “Ambersons” is a technically impressive movie that film students and historians love analyzing shot by shot. Unfortunately for Welles, you can only have one breakthrough, and “Ambersons” has enough shared DNA with “Kane” to make comparison unavoidable. Ultimately, I didn’t care for the film: too dense and complex for a first viewing, and not engaging enough to warrant a second. Each individual scene is well-crafted (and beautifully shot), but strung together they don’t make a cohesive movie. Obviously, the studio’s extensive retooling doesn’t help matters at all, which makes “Ambersons” infamously flawed; the ultimate “What If?” of American film. “Ambersons” earns its NFR standing on its reputation, but this one is reserved solely for film buffs enticed into exploring Welles’ filmography.

Shout Outs: An homage that made me laugh out loud; one of the film’s major events is announced on the front page of the Indianapolis Daily Inquirer, the fictional newspaper from “Citizen Kane”. There’s even a column by Jed Leland, Joseph Cotten’s “Kane” counterpart; no doubt a write-up on “dramatic crimiticism”.

Everybody Gets One: Dolores Costello was the best-known of the film’s stars at the time of release, with a film career that spanned over 30 years. Costello was primarily a silent film actor (dubbed “the Goddess of the Silent Screen”), and made the transition to sound film. “Ambersons” was one of her last movies before she retired from show business to focus on her family. Fun Fact: Dolores was married to John Barrymore, and is the grandmother of Drew Barrymore.

Seriously, Oscars?: Despite its troubled production and mixed reception, “Magnificent Ambersons” received four Oscar nominations. The film lost Picture, Supporting Actress, and Cinematography to that year’s juggernaut “Mrs. Miniver” (not to be confused with this movie’s Minifers), and lost Art Direction to another wartime drama: “This Above All”.

Other notes

- How did all this trouble start for Orson Welles and his “Magnificent Ambersons”? When Welles signed with RKO in 1939, his initial contract was a two-picture deal that gave him total creative freedom, including final cut. After a few false starts with other projects, Welles’ first film – “Citizen Kane” – was released in May 1941, but by then his contract had lapsed, and he had to renegotiate. Exasperated by his work ethic during “Kane” (and the ongoing controversy with William Randolph Hearst), RKO wrote up a new contract that gave Welles significantly less freedom, including the removal of his final cut privileges. Put a pin in this: It will definitely come back later.

- Right out the gate, you can’t help but make “Kane” comparisons. Both movies begin with a silent title card, which goes straight into the movie. It’s a bad idea to start any movie in a way that makes an audience think, “Hey that’s just like in ‘Citizen Kane’.” You’re just setting yourself up for disappointment.

- The opening prologue is verbatim the opening passages from the book: a description of the by-gone simplicity of 1870s American life. This sequence does, however, go on for a while. We get it, the past was better! Move on! Also, the whole opening is filmed with a fuzzy haze around the edges, kinda like when I do a bad job of cleaning my glasses.

- As expected, Welles excels at economic storytelling, especially in these opening scenes, packing in a lot of character detail and world building in a few choice compositions. Perhaps he packs a little too much in; I don’t know if all this upfront exposition makes the film too top-heavy, or if a 1942 audience was just more literate than me and could follow all of this.

- There’s a lot of great dialogue in this movie, but my favorite is George explaining to Lucy his Uncle Jack’s political status: “The family always likes to have someone in Congress.”

- I was ready to once again tip my hat to “Kane” cinematographer Gregg Toland and his masterful work filming “Ambersons”, but it turns out he wasn’t this movie’s cinematographer! Toland was unavailable, so Welles selected Stanley Cortez, known for his efficient, economic style, on loan from Universal (while utilizing many of Toland’s assistant camera team). Welles allegedly found Cortez so difficult to communicate with he demoted Cortez to second-unit photographer, letting his assistant Harry Wild preside over the remainder of the shoot.

- Tim Holt is obviously the Orson Welles stand-in as George, a spoiled rich kid not-unlike Charles Foster Kane. He’s very good in this, with significantly more screen time than his other NFR entries, but he lacks the charisma and star power Welles used in “Kane” to successfully engage an audience with his unappealing character. Welles had played George in a “Campbell Playhouse” radio adaptation a few years earlier, and as good as Tim Holt is, you do wish that Welles had taken on the part himself. Coincidentally, Orson’s real first name was George; Orson was his middle name.

- Why does George pronounce it “autoMObile”? It’s weird, especially considering that everyone else in the movie says “AUTomobile”. And if he hates cars now, wait until he sees “Two-Lane Blacktop“.

- So much of the attention in this film goes to the technical side that I don’t have a lot to say about this cast. Joseph Cotten and Dolores Costello are both good, but also just kinda there. And while Lucy is your standard ingénue part, it’s nice seeing Anne Baxter play something other than Eve Harrington. And she’s a lot better here than she is in “The Ten Commandments“, that’s for sure.

- So Orson loves big sprawling mansions and innocent scenes of playing in the snow. Got it. Perhaps Welles’ own Rosebud isn’t too far off from Kane’s.

- Longtime readers know I love me a one-take scene, and this movie has plenty of them. “Ambersons” uses a similar technique used later in “The Heiress“: plant the camera and let the characters move around. It prevents scenes from becoming stagnant while retaining the energy of a single take.

- Everybody loves Agnes Moorehead as George’s Aunt Fanny, and her character is certainly the most sympathetic of the bunch. Personally, I found her performance too theatrical, but then again most of Ms. Moorehead’s best performances were. Fanny’s famous water heater breakdown scene is especially scenery-chewing, but I’m willing to admit that I wasn’t too invested in the movie by the time that scene came along. Ah well, Moorehead did quite alright without hearing my dramatic crimiticisms.

- I went into this viewing knowing of the film’s troubles, most notably the alternate “happy” ending. You can almost pinpoint the exact moment where Welles’ film ends and the studio sanctioned ending begins. It’s not a total 180 from the rest of the movie, but you can sense that things are different. Everyone becomes a little too conveniently optimistic as the film segues into an upbeat conclusion. Somewhat ironically, this new ending is closer to the novel’s ending than Welles’ adaptation.

- The end credits are unique in that in lieu of on-screen titles they are all narrated by Orson Welles with visuals matching each craft (a camera for cinematography, etc.) This is very similar to how Welles would narrate the credits at the end of his radio programs. Conspicuously absent is any credit for a film score: Bernard Herrmann requested his credit be removed after most of his score was trimmed by the studio. Also, I noticed the “all persons fictitious” disclaimer at the very end. This had been around in movies for a while at this point, but I suspect its prominent inclusion here is a conscious effort by RKO to avoid another Hearst-esque headache.

Legacy

- When “Magnificent Ambersons” finished filming in January 1942, Welles flew to Brazil to work on his next movie “It’s All True”. By February, editor Robert Wise finished a rough cut and sent it to Brazil for Welles’ feedback (Wise wasn’t able to fly there himself due to wartime travel restrictions). This cut ran roughly 132 minutes, with Welles intending to do some trimming after a pair of sneak previews in March. The audience reception at both previews were extremely mixed (RKO president George Schaefer called it the worst screening he had ever been to) and a nervous RKO, too impatient to wait for Welles to return from Brazil, exercised their contractual right to cut the final film. Over 40 minutes of footage was deleted (up to 50 by some accounts), surviving sequences were trimmed and re-ordered, and multiple scenes were re-shot that April without Welles’ involvement or approval, including the aforementioned new ending. The final film was released in July 1942, and while it did okay with critics and audiences, it failed to recoup its investment, and Welles was unceremoniously fired from RKO.

- The only good thing to come out of the “Ambersons” re-shoots is that it was the first directorial work for Robert Wise, who would shortly thereafter pivot to directing, with such classics as “West Side Story” and “The Sound of Music” in his future. Welles felt betrayed by Wise filming the re-shoots, and the two did not speak to each other for 40 years, only reconciling shortly before Welles’ death.

- As Orson Welles started to get a reappraisal from the film world in the 1950s, so did “Magnificent Ambersons”, with some scholars even declaring it better than “Citizen Kane”. Although he always resented what RKO did to “Ambersons”, Welles eventually came around to accepting the final film, even tearing up when watching it on TV. In the early 1960s, Welles attempted to film an epilogue with the surviving cast, but the project fell through.

- The deleted portions of “Magnificent Ambersons” have been declared the “holy grail” of lost film footage. All signs point to the scrapped footage being destroyed by RKO to free up space in their vaults, but rumors of a surviving rough cut in Brazil still persist. There have been multiple efforts over the decades to find the missing footage, and even a few attempts at recreating the lost footage using the film’s continuity script, but so far nothing has come up. I’m surprised there hasn’t been a #ReleaseTheWellesCut campaign, though I guess first there needs to be a #FindTheWellesCut campaign.

- The closest we’ve ever gotten to the original cut of this film is a 2002 TV movie using Orson Welles’ original screenplay. Directed by “Like Water for Chocolate” helmer Alfonso Arau, this “Ambersons” still manage to deviate from both of its source materials and was quickly forgotten.

- And finally: the only reference to “Magnificent Ambersons” in pop culture that I can think of off-hand is an episode of “Mystery Science Theater 3000” where Tom Servo convinces himself he’s watching “Ambersons” to get through the bad movie they’re riffing on. “I don’t even like ‘The Magnificent Ambersons’!” You and me both, Servo.

Further Viewing: This is not the first time “The Magnificent Ambersons” was adapted for film. 1925’s “Pampered Youth” was an earlier stab at a film version, and like Welles’ later incarnation, most of this film’s footage is lost. I’m beginning to think this book is cursed or something.