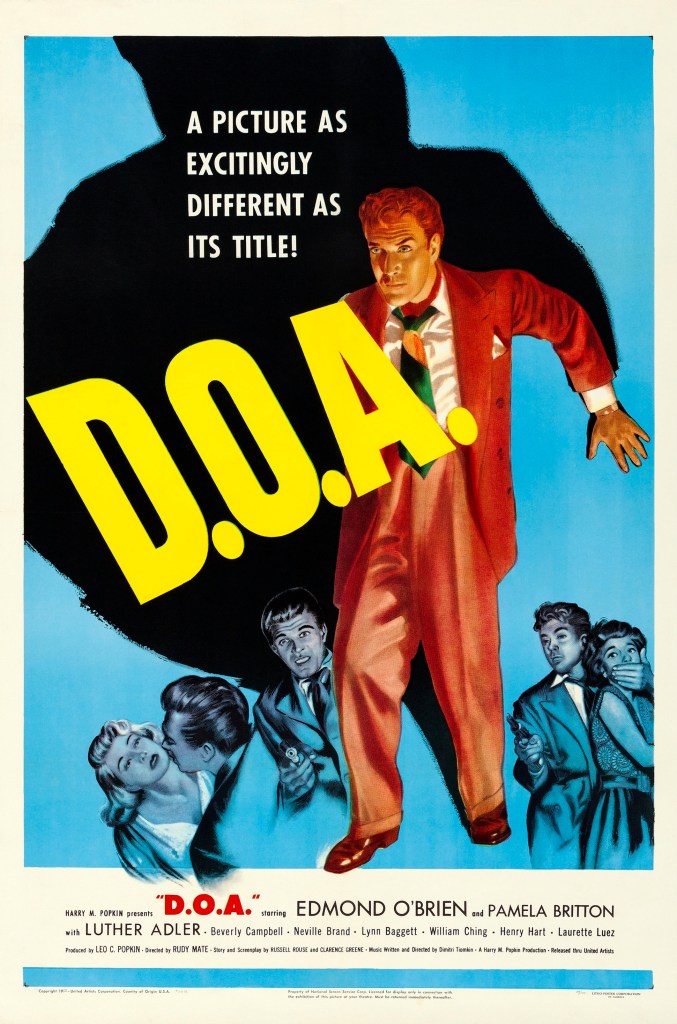

#789) D.O.A. (1950)

OR “Twenty-Twenty-Twenty-Four Hours to Go”

Directed by Rudolph Maté

Written by Russell Rouse and Clarence Greene

Class of 2004

The Plot: Frank Bigelow (Edmond O’Brien) walks into a police station to report a murder…his own! We flashback to a few days earlier; Bigelow is a successful accountant and notary public in Banning, California. On a whim, Bigelow flies up to San Francisco for some R&R and ends up going to a local nightclub with some newfound friends. The next morning, Bigelow wakes up to what he thinks is a hangover, but a trip to the doctor reveals he ingested a “luminous toxin” with no known antidote and only 24 hours to live! With the help of his faithful secretary Paula (Pamela Britton), Bigelow retraces his steps to determine who would want to poison him and why. Will Bigelow find his killer, or will he end up…Dead On Arrival?

Why It Matters: The NFR calls the film “fast-paced and suspenseful”, saluting O’Brien’s performance and praising the film for being “more cynical than the average film noir”.

But Does It Really?: “D.O.A.” is not without its flaws, but if you’re willing to go along with it, it’s still watchable over 75 years later. We have plenty of B movies on the Registry (including another one starring Edmond O’Brien), but “D.O.A.” is just well known and respected enough that an argument could be made for its NFR inclusion. Plus it’s got on-location footage of downtown L.A.; hardcore cinephiles eat up L.A. footage like catnip. Slightest of passes for “D.O.A.” on the “N.F.R.”

Everybody Gets One: Hailing from what was then Austria-Hungary (now Poland), Rudolph Maté quickly rose the ranks to become a prominent cinematographer in Europe, most notably for Carl Theodor Dreyer’s “The Passion of Joan of Arc”. A move to Hollywood in the mid-1930s saw Maté serve as cinematographer for a number of NFR titles, including “Dodsworth” and “Gilda”. During production of 1947’s “It Had to Be You”, Maté started taking over directorial duties from Don Hartman (I’m not sure why), earning a co-directing credit. “D.O.A.” was Maté’s third film as a director, following his first solo effort, fellow noir title “The Dark Past”.

Seriously, Oscars?: No Oscar nominations for “D.O.A.”, but many of the film’s major creatives had brushes with the Academy. Rudolph Maté received five Oscar nominations throughout his career for his cinematography (including for “The Pride of the Yankees”), Edmond O’Brien went on to win Best Supporting Actor for “The Barefoot Contessa”, and screenwriters Clarence Greene and Russell Rouse took home Oscars as part of the “Pillow Talk” writing team.

Other notes

- This film had quite a few “WTF” moments for me, and the first came right after the opening credits. When Bigelow flashes back to a few days earlier, the fade to another scene includes a shot of what appears to be water swirling down a drain. Are they filming the inside of a toilet? Did the ripple effect not exist yet? It’s a weird choice I haven’t seen in any other movie and it threw me for a bit of a loop.

- After watching him oscillate between lead roles in the B pictures and supporting roles in the A pictures, I consider Edmond O’Brien the Avis of leading men: He’s not number one, but he tries harder. Also, “D.O.A.” continues a weird trend in NFR films where Edmond O’Brien’s character’s occupation is something mundane, yet always leads to adventure and danger. He’s an accountant and notary public here, a life insurance investigator in “The Killers”, and a US Treasury agent in “White Heat”. What’s next, a renegade patent examiner?

- One of the film’s major attributes, especially for its time, is on-location footage of both San Francisco and Los Angeles. As a former resident of San Francisco, I love seeing this old footage of the city back in the ‘50s. One question: What was Market Week? It looks like a busy celebration in this movie that brings in lots of out-of-towners. I remember Farmers Market on Embarcadero, and I remember Fleet Week, but I don’t recall Market Week.

- This is one of those movies that is so of its time, this post could just be one long “Wow, That’s Dated” segment. Movies in the late ‘40s/early ‘50s had a different vibe to them. I can’t quite articulate it, but it was just a completely different way of living than we’re used to now. Everything was just fancier, from how people interacted with each other to the overall aesthetics. It’s a little like watching “The Twilight Zone”.

- Perhaps the film’s most dated moment: a musical interlude with those jive-crazy Fishermen. The scene is entertaining, but it begs the question: Why are the shortest movies always the ones with the most padding?

- Easily the most unrealistic part of this movie: Bigelow just hopping onto a cable car. Where’s your Clipper Card? Speaking of San Francisco, that’s Grace Cathedral on Sacramento Street that Frank walks by on his way to the doctor. It’s a beautiful view, but that also means Frank just walked up the steepest, longest staircase I’ve ever endured. He should be a puddle of sweat by now. And while he’s there, there’s a really good Tiki bar about a block away. He should check that out before he dies.

- Bigelow gets two different sets of poison tests from two different doctors? I hope his health insurance covers all of this. On a related note, the doctor Bigelow gets his second opinion from is played by Frank Gerstle, a craggy-faced character actor who has made a few appearances throughout the NFR. I know him best for a film of his that got the “MST3K” treatment, playing a much less helpful doctor in “The Atomic Brain”.

- I don’t have much to say about Pamela Britton’s work as Paula, other than she does okay with the limited role of “girl Friday”/pseudo-love interest. Britton’s filmography is scarce (she worked primarily on the stage), but she got her due in the ‘60s with a regular role on “My Favorite Martian”.

- Another very unrealistic story beat: Flying from San Francisco to Los Angeles is not that easy. Maybe back then, but definitely not now. I imagine airports back then were like taxi stands: a row of planes just lined up waiting for passengers to hop in. “Fly me to L.A. my good man, and step on it!”

- Halliday’s secretary is played by Beverly Campbell, who shortly after this film would revert back to her maiden name, Beverly Garland, and find success on TV, most notably on “My Three Sons”. And hey, she’s got an “MST3K” connection, too! Garland pops up in both “Gunslinger” and “It Conquered the World”.

- Like I said, cinephiles love when L.A. plays itself in a movie (Hell, there’s a whole movie about it). As we venture into downtown L.A., you’ll notice several shots prominently featuring the Million Dollar Theater, one of the earliest movie houses in the U.S. – built by no less than Sid Grauman. At the time of filming “D.O.A.”, the Million Dollar Theater was owned by Harry Popkin, also known as…the producer of “D.O.A.”!

- As the plot points start to pile-up on each other in the second half, I started asking, “Am I supposed to be following any of this?” This movie is 90 percent MacGuffins, with Bigelow following each new lead until something else gets his attention. Is this film moving too fast or am I moving too slow?

- Shoutout to Luther Adler as Majak, the man who may be behind all of this…or not. Adler was primarily a stage actor, and was one of the original members of the Group Theater along with his sister, Stella Adler. “D.O.A.” was one of only a handful of films Adler appeared in, but as a testament to his clout in the acting world, he gets third billing in this movie for essentially one scene. Either that or he had a great agent.

- What the hell is going on with Majak’s henchman Chester? Neville Brand is giving an unhinged performance that, while entertaining, is throwing the movie out of whack (similar to Dennis Weaver in “Touch of Evil”). And why does he keep talking in the third person? Is he George Costanza? Chester’s gettin’ upset! Side note: Neville Brand gives us our third “MST3K” connection…well sorta: He’s in “Angels Revenge” but his scenes were all cut for the “MST3K” version.

- As Frank and Paula have their dramatic scene on a street corner professing their love for each other, all I could think was “Get out of the streets! They are trying to kill you!” They couldn’t hear me though because, ya know, it’s a movie.

- The scene where Majak and his men hunt down Bigelow on a bus is probably why L.A. doesn’t have reliable public transit anymore.

- The film’s ending wraps everything up a little too quickly, but we get a reprieve of that weird “swirling toilet” flashback thing! And to top it all off, after “The End” we get a disclaimer attributed to Technical Adviser Edward F. Dunne, M.D.: “The medical facts in this motion picture are authentic. Luminous toxin is a descriptive term for an actual poison.” What is happening!?

Legacy

- “D.O.A” was released in April 1950, receiving decent reviews and box office before more or less disappearing. The film, however, got an interesting reprise almost 30 years later thanks to the wacky world of U.S. copyright law. Up until 1992, films had to have their copyright renewed every 28 years. When Cardinal Pictures tried to get the copyright of “D.O.A.” renewed in 1978, they learned that the film was actually copyrighted in late 1949, meaning that the copyright expired in 1977 and the film had already slipped into public domain. The film’s newfound public domain status led to it being played more often on TV, giving the film a reappraisal by a new generation of movie lovers.

- Rudolph Maté continued directing film up until his death in 1964. Later entires in his filmography include “When Worlds Collide” and “The 300 Spartans”, the latter of which inspired the graphic novel “300” and its subsequent film adaptation.

- “D.O.A.” is one of three NFR titles to be overdubbed by the short-lived ‘80s TV show “Mad Movies” (the others are “Cyrano de Bergerac” and “Night of the Living Dead”). The writers decided that Edmond O’Brien looks like Desi Arnaz, so the whole episode is an extended “I Love Lucy” parody. I think the O’Brien/Arnaz connection is a stretch, but it’s always great finding an excuse to reference “Mad Movies” on this blog.

- On a related note: “D.O.A.” recently received another parody commentary track, this time courtesy of Bridget Nelson and Mary Jo Pehl at Rifftrax. Clearly I am not the only person who felt the need to make fun of this movie.

- Another advent of the film’s public domain status is its frequent remakes and/or movies that can steal heavily from “D.O.A.” without paying anyone, most notably a 1988 remake with Dennis Quaid and Meg Ryan. Among the others, I saw the 2006 pseudo-remake “Crank” years ago. It has elements of “D.O.A.” mixed with “Speed” and is…well it’s awful, there’s no two ways around it. And somehow there’s a sequel?