#746) With the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in Spain (1938)

Directed by Herbert Kline and Henri Cartier-Bresson

Class of 2017

Well, here’s another subject I am not qualified at all to discuss: The Spanish Civil War. As always, this post can only offer an oversimplified account of the Spanish Civil War through the lens of this movie, and I encourage anyone interested in these events to do further research.

Thanks as always to Benjamin Wilson for tracking down this obscure NFR title, which can be viewed online at the Spanish Civil War Virtual Museum.

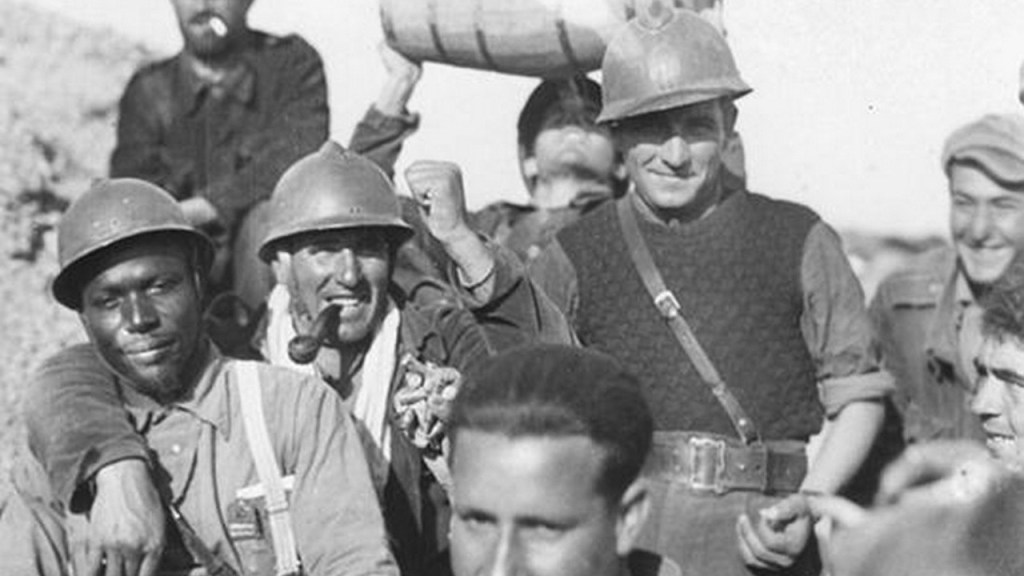

The Plot: In 1936, the Second Spanish Republic was threatened by an attempted coup from the right-leaning Nationalist faction, leading to the Spanish Civil War. Although the Nationalists were gaining traction thanks to the rise of Fascism in Europe, the Republic maintained control of Spain’s major cities (for the time being) and received support from several other countries through a group of international brigades and battalions. One brigade which included 2800 American volunteer fighters was known as the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, who fought for the Republic in seven battles through 1937 and 1938. The early days of this brigade were filmed by Herbert Kline and Henri Cartier-Bresson and screened in America as a fundraiser to bring our wounded soldiers home.

Why It Matters: The NFR offers no superlatives about this film, with the write-up solely consisting of its historical backdrop, plus a shoutout to NYU’s Tamiment Library and the Abraham Lincoln Brigades Archive.

But Does It Really?: A “historically significant” yes on this one. I knew nothing about the Spanish Civil War going into my viewing, and I appreciated the opportunity to learn more about it, albeit from the point of view of American volunteers and not, ya know, the Spanish citizens fighting for their own country’s future. “With the Abraham Lincoln…” paints a unique picture of America supporting another country in an oft-overlooked war, and simultaneously serves as a precursor of sorts to the strong-armed propaganda the US would start cranking out once we entered WWII. I’m glad the NFR found a place for “With the Abraham Lincoln…” on the list, and equally glad that it can be easily viewed online.

Everybody Gets One: Like many other Americans in the 1930s, writer Herbert Kline was concerned about the ongoing rise of Fascism in Europe, traveling to Spain to volunteer his support. While working at an English language radio station in Madrid, Kline was approached by photographer Geza Karpathi about making a movie about the war for the New York based Frontier Films. Neither man had any prior filmmaking experience, but still managed to create 1937’s “Heart of Spain”. For his next film “Return to Life”, Kline teamed up with Henri Cartier-Bresson, a celebrated photographer known for capturing candid moments of his world travels. While working on “Return to Life” the two were commissioned by Frontier Film and the American Medical Bureau to Aid Spanish Democracy to film a short about the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. Kline and Cartier-Bresson traveled throughout Spain with the Brigade in the summer and fall of 1937, while simultaneously working on “Return to Life”. Kline said in later interviews that while he and Cartier-Bresson co-directed their films, he focused more on the writing while Cartier-Bresson had the overall creative vision.

Seriously Oscars?: No Oscar love for this movie, though Herbert Kline would eventually receive a nomination for his 1975 documentary “The Challenge…A Tribute to Modern Art” (his 1971 documentary “Walls of Fire” also received an Oscar nomination, though it was the producers and not Kline who were nominated).

Other notes

- The XV International Brigade was one of many organized to fight for the Republic during the Spanish Civil War, uniquely consisting primarily of English-speaking volunteers from America, England, and Canada. One dominantly American battalion within the brigade was the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, and the name went on to become the widely accepted nickname for the entire brigade.

- In addition to the footage shot by Kline and Cartier-Bresson, “With the Abraham Lincoln…” includes newsreel footage shot by Jacques Lemare and Robert Capa, the latter also serving as the production’s still photographer.

- For those of you with no interest in wartime propaganda, please accept footage of the soldiers using shower equipment supplied by the French Steel Workers Union, complete with rear nudity!

- I appreciate that this movie identifies many of the soldiers featured on screen, typically flashing their name, city, and occupation on a corresponding intertitle. Points deducted, however, for not identifying the one Asian soldier in this whole movie. Come on, you gave him a close-up!

- Among those who visit the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in this film is Congressman John T. Bernard, one of only a handful of US House Representatives to vote against the various Neutrality Acts passed by Congress in the 1930s to stay out of any European conflicts (acts that this movie deems “shameful”). Note to Congressman Bernard: If you’re going to support anti-fascist movements, lose the Hitler mustache.

- Despite being a film commissioned by the American Medical Bureau, the AMB only gets one shout-out about halfway through the movie for the ambulances they provided to our overseas soldiers. I don’t know how much input the AMB had on this film, but they did not get enough bang for their buck.

- One sequence that often gets singled out in articles and essays about the film is when our wounded soldiers gather to watch a local game of soccer (Er…football). It’s a nice bit of levity after all this uber-patriotism and shots of war.

- Of the soldier idents, my favorite is Maurice Nickenburg from Brooklyn, described as being “active in the theater”. Is it just me or does that sound like a euphemism?

- A special section towards the end celebrates Robert Raven, a veteran of the Lincoln Brigade who lost his sight during a battle. His name receives the boldest text possible, and he is hailed as “[o]ne of the greatest American heroes of modern times”.

- “With the Abraham Lincoln…” concludes with the hard sell urging viewers to donate to the cause, stating that $125 can bring one wounded American soldier home. That’s about $2700 in today’s money; a tall order for a nation that was still recovering from the Great Depression. In my research I couldn’t find a single write-up confirming if this film helped raise money or not.

Legacy

- The good news: the Spanish Civil War ended in April 1939. The bad news: the Nationalists won, with their fascist reign lasting through the death of Generalissimo Francisco Franco in 1975. Shortly after Franco’s death, Spain transitioned to a constitutional monarchy, which gave their king (Juan Carlos I) less authority than he had prior to the Spanish Civil War. Spain continues to have a constitutional monarchy, and as of this writing, Generalissimo Francisco Franco is still dead.

- The Abraham Lincoln Brigade went by several names during its short tenure, owing to its conflation with other brigades as they faced growing casualties. The last known surviving member of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade was Delmer Berg, who also served in the US Army during WWII, and died in 2016 at age 100.

- Both Herbert Kline and Henri Cartier-Bresson continued making films along the lines of “With the Abraham Lincoln…”; documentary shorts and features that supported anti-fascism and/or highlighted underrepresented cultures. Kline died in 1999 at 89 years old, Cartier-Bresson in 2004 at 95.

- “With the Abraham Lincoln…” was not released theatrically in the traditional sense, but rather 16 mm prints were screened in union halls and other meeting spots for pro-Republic groups in America. The film fell into obscurity in the ensuing decades (even the filmmakers forgot they had made it) and was considered lost until one of these 16 mm prints was discovered at the Veterans of the Lincoln Brigade office in 2010 by film scholar Juan Salas.