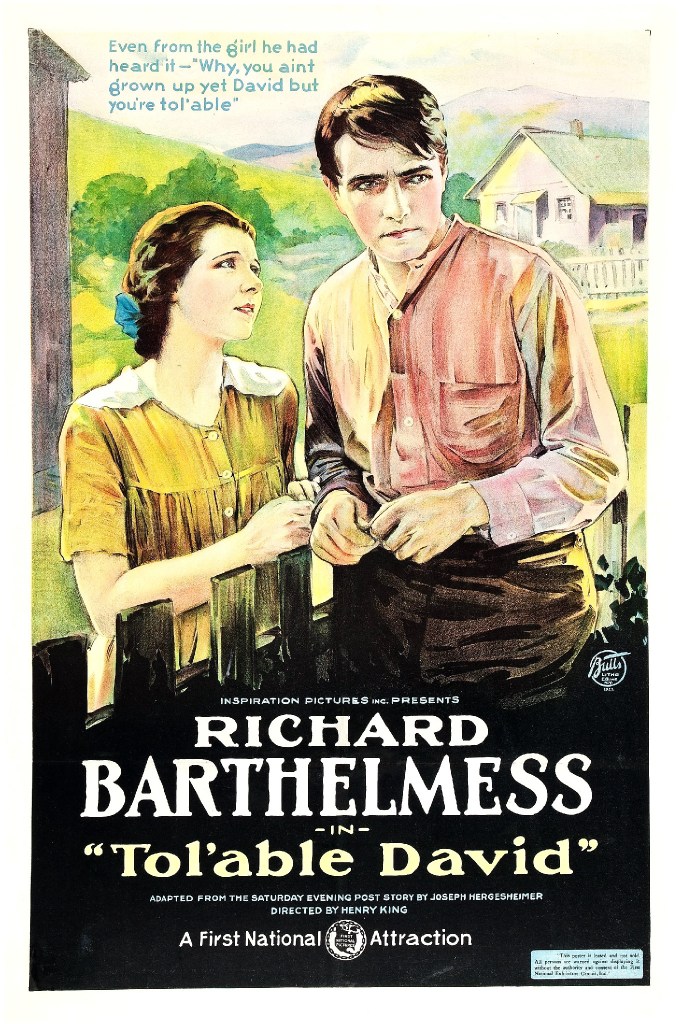

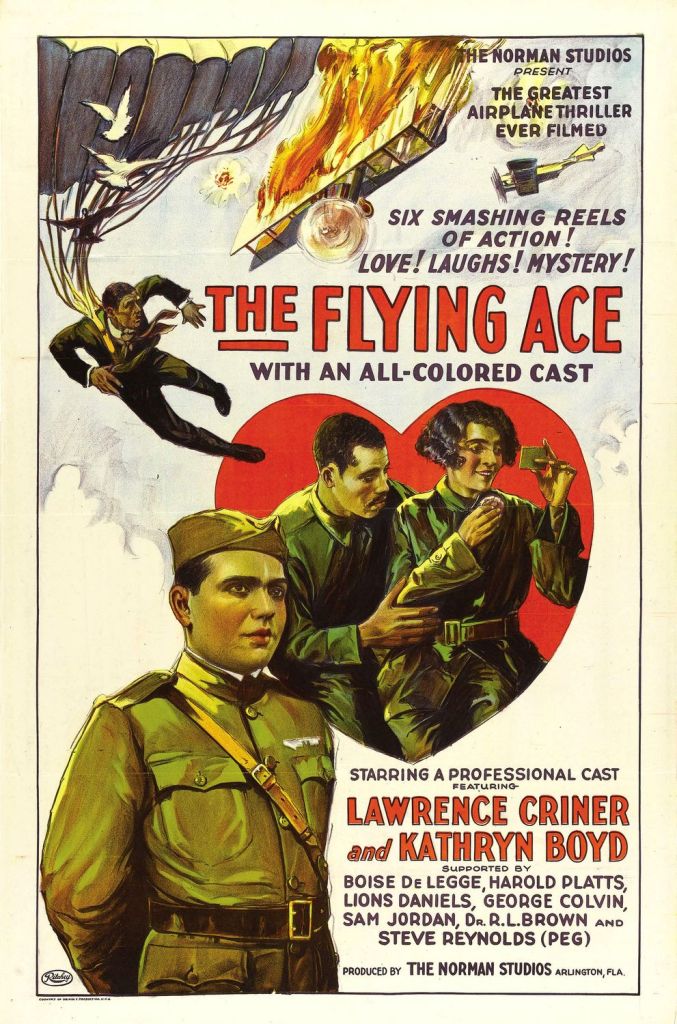

#695) The Flying Ace (1926)

OR “Caper Planes”

Directed & Written by Richard Norman

Class of 2021

The Plot: Captain Billy Stokes (Laurence Criner) is a former fighter pilot (nickname “The Flying Ace”) returning home to Mayport, Florida to resume his job as a detective for the Florida East Coast Railway. Billy is immediately assigned to investigate the disappearance of Blair Kimball (Boise De Legge), the railroad’s paymaster who was kidnapped upon his arrival in Mayport, along with his briefcase containing $25,000 in payroll. The prime suspect is station master Thomas Sawtelle (George Colvin), though his daughter Ruth (Kathryn Boyd) insists on his innocence. Billy is also suspicious of Finley Tucker (Harold Platts), a local pilot whose marriage proposals to Ruth have been repeatedly turned down. But this mystery is more or less an excuse to shoehorn in some ’20s aviation, and to showcase the talent of – as the opening credits put it – an “Entire Cast Composed of Colored Artists”.

Why It Matters: The NFR calls the film itself “a fairly straightforward romance-in-the-skies drama” but praises its “compelling cast and good production values.” They also consider the film “an excellent example” of the kind of race films Richard Norman was making.

But Does It Really?: As a movie, “Flying Ace” is fine; not incredible, but an interesting viewing experience. More interesting to me, however, was the history of Norman Studios, the company behind this film. While founded and operated by a White man, Norman Studios was known for race films, cast entirely with Black talent, made for a Black audience, and devoid of the harmful stereotypes still prevalent in other films of the day. “Flying Ace” is all that survives from Norman Studios’ output and makes the NFR for its representation of an all but forgotten era of filmmaking.

Everybody Gets One: Richard Norman started his film career in the 1910s making “home talent” films: travelling from town to town, filming local talent, splicing that footage into a pre-existing film, and screening the results at their local theater (not unlike “The Kidnappers Foil“). By the early 1920s, Norman recognized the untapped potential in the country’s Black moviegoing audience and pivoted to race films. He moved to Jacksonville, Florida and purchased Eagle Film Studios, renaming it Norman Studios. Norman made five films throughout the 1920s, all of them utilizing the talents of local Black actors. The only one of these race films to survive in its entirety is “The Flying Ace”.

Wow, That’s Dated: The lost profession of railroad detectives. Back when railroads were the most modern form of transportation, stations had difficulty staffing enough of their own police and security to prevent crime, so detective agencies would often loan out their members. Even by the time “Flying Ace” was made, railroad detectives were on their way out, mainly due to railroad companies beefing up their own police units, but also in part because of the decline in commercial railroad travel. Oh the irony of this movie having a railroad detective who is also a pilot and making his own job obsolete.

Other notes

- “The Flying Ace” was filmed in Florida primarily at and around Norman Studios in Arlington, a region of Jacksonville, as well as the nearby community of Mayport. This movie contains one tell-tale sign that all movies shot in Florida share: you can see actors genuinely sweating on-screen. Not fake movie sweat applied right before a take, but honest-to-goodness perspiration from the Florida sun. This aggressive act of human biology also crops up in a lot of films from the late ’80s/early ’90s when the likes of Disney and Universal tried to turn their movie studio theme parks into working movie studios. Turns out you can truly never beat the heat.

- This film was partly inspired by Bessie Coleman, the famous aviator who five years earlier had become the first African American woman to hold a pilot license. Coleman had corresponded with Richard Norman about making a movie together, but sadly Coleman died in a plane crash just a few weeks before “Flying Ace” started filming. Whether or not Colman was supposed to be in the film is lost to time, but she definitely had an influence on the character of Ruth and her fascination with airplanes.

- Most of the cast were talent from local theaters. Lawrence Criner and Kathryn Boyd were members of the Lafayette Players, Sam Jordan (seen here as the dentist Dr. Maynard) was part of a vaudeville team, and Lions Daniels (Constable Splivins) was – according to the film’s press release – “better known on stage as ‘Skunkum Bowser’.” I have no idea what that means, but I assume it’s offensive.

- Adjusted for inflation, the $25,000 stolen payroll would be about $440,000 today.

- “Contrary to women’s customs, Ruth was on time.” Boooooooo.

- Thanks to Finley’s detailed instructions to Ruth, I feel very qualified to pilot a biplane should that situation ever arise.

- With so much of the movie centering around planes, I was hoping for some fun flight scenes. Disappointingly, all the flying scenes are clearly shot on the ground with a dummy plane and presumably a fan to simulate the wind. There is a single shot of a plane in flight, filmed on the ground, and probably tacked on from an entirely different movie. “Wings” this ain’t.

- Billy just got home from the war? It’s 1926, the Armistice was eight years ago. Where the hell has he been?

- Billy’s assistant Peg is played by Steve Reynolds, a Norman Studios regular who in real-life had lost his right leg in a work accident. Reynolds is credited here as Steve “Peg” Reynolds, which is just adding insult to injury in my book. Though I guess it’s still better than going through life as “Skunkum Bowser”.

- Something I noticed about Billy: he always points with both his index and middle fingers. Did he work in customer service?

- Up until this viewing I was unfamiliar with cane guns, such as the one that Peg has hidden in his crutch. I was also unaware of the extra-long barrel cane guns have, which made for an unintentionally hilarious reveal as Peg pulls out an absurdly long handgun. We won’t see a gun this long again until the Joker in the 1989 “Batman”.

- The scene where Billy sums up the solution to the crime highlighted something interesting for me: detective movies can’t really work in a silent film. As expected, Billy has a long monologue where he points out all the clues and determines who did it, which means a lot of expository intertitles breaking up what is already a visually uninteresting scene.

- [Spoilers] One of the kidnappers is Constable Splivins! A corrupt cop as the bad guy in your movie? Better get that in before the Production Code shows up.

- Once Billy solves the case, the bad guys make their getaway under the cover of broad daylight, despite the previous scene establishing it as nighttime. This is where color tinting your film comes in handy.

- I just watched a one-legged man open fire on a car with his comically long handgun while pursuing the criminals on his bicycle. That’s gonna be the most impressive thing I see for a long while.

- The movie’s climax is a chase scene between Billy and Finley in their respective planes, which has got to be a cinematic first (take that, “Sky High“). While this flight scene is still very much an earthbound production, Norman and his crew get creative with their shots, such as rotating the camera to make it look like Finley’s plane is flying upside down.

- Wait, Billy and Ruth end up together? There was zero hint at a romance before this ending; you can’t just sneak one in at the last minute. No fair!

- So when does Snoopy show up in this to take down the Red Baron?

Legacy

- By the late 1920s film had all but converted to sound. Although Richard Norman had invested in a “sound-on-disc” system, the rival “sound-on-film” format quickly became the norm. This misstep, mixed with the film industry’s relocation to Hollywood, as well as Florida politicians launching an anti-film campaign, led to the decline of Norman Studios. While his feature film output ended with 1928’s “Black Gold”, Richard Norman continued making industrial shorts up until his death in 1960.

- After Richard Norman’s death, his wife Gloria used the studio as a dance school before finally selling it in 1976. Over 20 years later, Jacksonville resident Ann Burt discovered that the buildings that once housed Norman Studios were still standing, albeit in terrible condition. Burt spearheaded a decades-long restoration and preservation effort, with Norman Studios being added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2014. Today, Norman Studios is a non-profit organization celebrating the building’s history and is the only surviving silent film studio in America.

- In the last decade, restored prints of “The Flying Ace” have made the film festival rounds, including the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, which I do not highlight on this blog as much as I should. “Flying Ace” can also be found online thanks to a print from the Library of Congress.