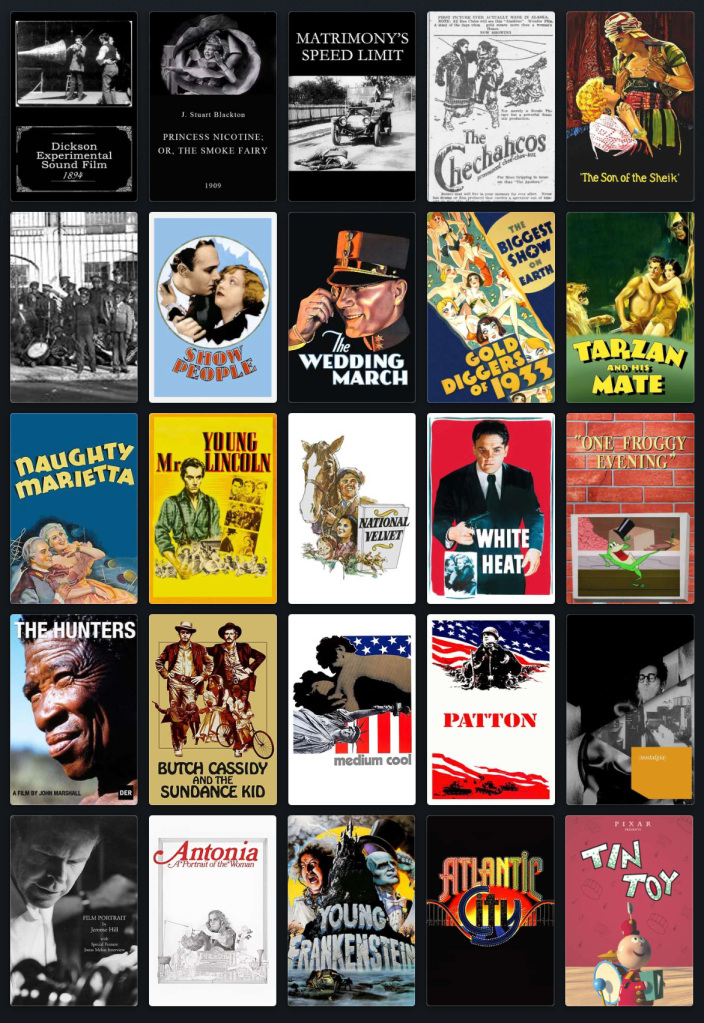

December 16th, 2003: Before heading off to midnight screenings of “Return of the King”, the Library of Congress throws 25 more movies into the National Film Registry, bringing the grand total to 375 films. I’ve just finished watching all 25, and here is my regular recap. In chronological order, here’s the Class of 2003:

- The Dickson Experimental Sound Film (1894): “the earliest known attempt to synch film with sound”

- Princess Nicotine; or, The Smoke Fairy (1909): “confusing, but man are those special effects a sight to behold.”

- Matrimony’s Speed Limit (1913): “not very entertaining today…[but] is one of a handful of surviving films from Alice Guy-Blanché”

- The Chechahcos (1923): “Its Alaskan production claim might be this film’s sole reason for making the NFR”

- The Son of the Sheik (1926): “I just don’t understand why the NFR didn’t induct “The Sheik” first (and as of this writing, still hasn’t).” “It don’t make no sense.”

- Fox Movietone News: Jenkins Orphanage Band (1928): “the only footage available online is 10 minutes of outtakes.” “Does the final newsreel still exist?”

- Show People (1928): “a funny love letter to early Hollywood.”

- The Wedding March (1928): “an intriguing behind-the-scenes story, but ultimately a viewing experience reserved solely for film buffs.”

- Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933): “how can you say no to the musical that gave us ‘We’re in the Money’?”

- Tarzan and His Mate (1934): “this Tarzan is a perfect representation of the overall series.”

- Naughty Marietta (1935): “the kind of escapist romantic movie musicals that delighted Depression-era audiences.”

- Young Mr. Lincoln (1939): “As a biopic it’s a bit on the nose…[a]s courtroom drama it’s a bit more engaging…[a]s a classic film worthy of preservation, I have my doubts”. [Note from the future: Jeez, that was harsh. I don’t remember hating this film that much, or at all.]

- National Velvet (1944): “a sweet, genuinely heartfelt movie”

- White Heat (1949): “an entertainingly tense, well-scripted entry in the [gangster] genre.”

- One Froggy Evening (1955): “still really funny with solid animation” “Who am I to say no?”

- The Hunters (1957): “I did not start this blog so I could watch a giraffe snuff film.”

- Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969): “a continuation of New Hollywood’s deconstruction of the classic Western”.

- Medium Cool (1969): “a chance to see what happens when [Haskell] Wexler has full control over a movie.”

- Patton (1970): “an iconic piece of filmmaking”

- (nostalgia) (1971): “deceivingly simple, yet quite thought-provoking.”

- Film Portrait (1972): “a thoughtful, entertaining memoir”.

- Antonia: A Portrait of the Woman (1974): “a tribute to an unsung artist who finally got her moment in the sun”

- Young Frankenstein (1974): “not only one of the funniest films ever, but also a frontrunner for best parody ever.”

- Atlantic City (1980): “I’m a sucker for a well-acted character study”

- Tin Toy (1988): “an important stepping stone movie in the history of Pixar”.

Other notes

- The big news at the time was the reauthorization of the National Film Preservation Act in November 2003 (cutting it a little close for that December announcement, but it all worked out). There weren’t too many amendments this time, other than language to encourage public accessibility to Registry titles, as well as their inclusion in the collection at the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center in Culpeper, Virginia. Also, in a surprising move, Congress actually gave the National Film Preservation Board more money! Appropriations to the NFPB at the time were $250,000 a year, with the reauthorization allotting $500,000 annually to the Board in 2004 and 2005, and then up to $1,000,000 a year through 2013. While those figures would get lowered again in a 2008 amendment, they wouldn’t be lowered to pre-2003 amounts, so that’s still a win for everyone.

- The NFR Class of 2003 is a continuation of the “minor classic”/“what isn’t on the list yet” path the Registry traveled for most of the 2000s. A few iconic titles are here, but mostly encores from artists already represented (another Cagney gangster pic, another Busby Berkeley backstage musical, another Mel Brooks comedy, etc). The Class of 2003 checks off a few more missing bits of American film history with a Tarzan movie, an Eddy/MacDonald musical, a Rudolph Valentino vehicle (though arguably the wrong one), and the first Pixar short on the list. In addition, the NFR still made room for films by such lesser-known filmmakers as Hollis Frampton, as well as unique titles like “Princess Nicotine” and “The Chechahcos”.

- My posts on these 25 films can be summed up in two words: “I guess.” There’s only a handful of these films that I unconditionally support for NFR inclusion in these write-ups, and the rest are a series of passes I gave for historical or cultural significance, with one or two whose inclusion I questioned outright. Once again: I don’t recall hating “Young Mr. Lincoln” that much, but that post was pretty early in my run so perhaps a re-watch is in order.

- Side note: In my “Atlantic City” post I slam anti-vaxxers a full year before the COVID-19 pandemic. I am nothing if not consistent.

- Shoutout to 1894’s “The Dickson Experimental Sound Film”, which at the time was the earliest film on the Registry. It would hold this distinction for seven years before being supplanted by the current record-holder: 1891’s “Newark Athlete”.

- At the time of the NFR announcement, “The Last Samurai” was number one at the U.S. box office. No current NFR titles were playing in theaters, but the sequel to one was: “The Matrix Revolutions”. Other notable titles in theaters included “Elf”, “Somethings Gotta Give”, “Master and Commander”, “School of Rock”, and “Love Actually” (which is mercifully ineligible for the NFR).

- Quite a few Double-Dippers in the Class of 2003. Among them: actors Peter Boyle, Cloris Leachman, and Kenneth Mars, art directors Cedric Gibbons and A. Arnold “Buddy” Gillespie, editor John C. Howard, and possibly Robert Z. Leonard (he has a cameo as himself in “Show People” and was the original director of “Naughty Marietta” for literally one day).

- Thematic double-dippers: Portraits (Both “Film” and “of the Woman”), historical biopics, extraordinary animals, unhappy engagements/arranged marriages, train robberies with explosives, the descendants of more famous characters, gold diggers both literal and figurative, entries set/filmed in Africa, pie fights, films made explicitly to test new technology, and the song “Ah! Sweet Mystery of Life”

- Favorites of my own subtitles: Fear and Loathing in Los Anchorage, Polly Parker Pranks a Pair of Pickled Patrons, Strong Arm of the Ma, Ol’ Blood and Guts is Back, Burn After Filming, and A Movie-able Feast.

- As always, I’m at a loss for how to end these recaps, so here’s Michigan J. Frog! It was either him or the “Tin Toy” baby, so consider yourself lucky.