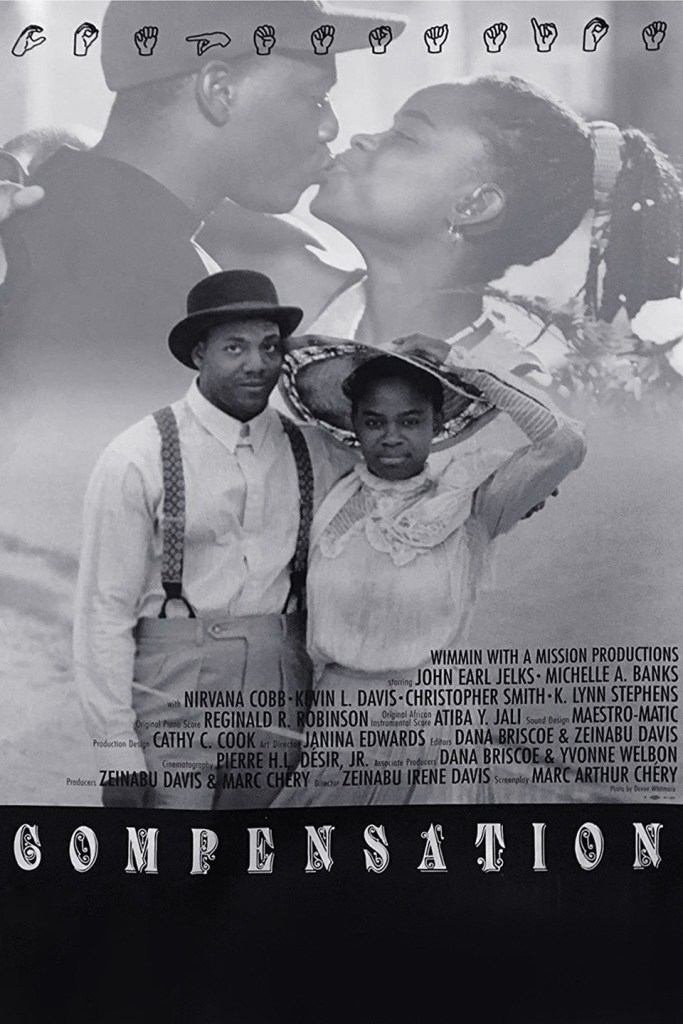

#792) Compensation (1999)

OR “What’s Your Sign?”

Directed by Zeinabu irene Davis

Written by Marc Arthur Chéry

Class of 2024

The Plot: Inspired by Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem of the same name, “Compensation” tells two love stories in two different time periods about African-Americans in Chicago, both between a deaf woman and a hearing man. In 1910, educated Malindy (Michelle A. Banks) teaches illiterate migrant worker Arthur (John Earl Jelks) how to read, and falls in love with him, despite her friends and family insisting that Arthur is beneath her. In 1993, librarian Nico (also John Earl Jelks) learns ASL to woo free-spirited Malaika (also Michelle A. Banks), who doesn’t date hearing men. As foretold in the Dunbar poem, the “boon of Death” comes for both of our couples; Arthur contracting tuberculosis in 1910, and Malaika living with an HIV/AIDS diagnosis in 1993. But “Compensation” transcends its slightly melodramatic story beats to paint a unique portrait of being Black and deaf on either side of the 20th century.

Why It Matters: No superlatives from the NFR write-up, other than the film’s “unusual narrative approach”. The write-up is primarily a rehash of the story, with some additional context from NFPB chairwoman (and TCM mainstay) Jacqueline Stewart. Points deducted, however, from the write-up for misspelling screenwriter Marc Chéry’s first name. There’s also an interview with Zeinabu Davis conducted by the Library of Congress, plus a photo of Davis and Chéry celebrating their NFR induction.

But Does It Really?: As always, I’m looking for NFR titles that stand on their own unique piece of ground, and “Compensation” more than fits the bill. Unlike a lot of noisier NFR entries, “Compensation” is a quiet, contemplative movie; the kind of stripped down character study I’m always fond of, especially when it’s this well made. With its original perspective of the Black deaf community and its parallel timeline aesthetics (all masterfully shot in black and white), “Compensation” tells its story beautifully and compassionately. A yes for “Compensation”, the kind of underrated film the NFR has helped to highlight and celebrate through the years.

Shout Outs: Davis has cited fellow L.A. Rebellion/NFR movies “Daughters of the Dust” and “Killer of Sheep” as influences on this film. And thanks to a brief sequence of Nico and Malaika deciding which movie to see, we get glimpses of what was playing at your local movie theater in 1993, including “Jurassic Park” and a re-release of “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” (which I saw!).

Everybody Gets One: Originally intending to earn a master’s degree in African studies, Zeinabu irene Davis would get an MFA in film and video production from UCLA in 1989. As part of the second wave of African-American filmmakers in UCLA’s famous L.A. Rebellion, Davis’ initial short films centered around the hardships of Black women in both the past and present, with such titles as “Cycles” and “A Period Piece”. “Compensation” was Davis’ first feature film, a collaboration with her husband, Marc Arthur Chéry, whom Davis met when they were both students at UCLA. And yes, the I in Davis’ middle name irene isn’t capitalized. I don’t know why, but if e e cummings can do it, so can she.

Title Track: As mentioned throughout the movie, the title comes from the 1906 poem by Paul Laurence Dunbar, who is described within the film as “America’s Negro Poet Laureate” of the early 1900s. The text of the poem is displayed and spoken throughout the film, including a version set to music and interpretive dance!

Seriously, Oscars?: Although “Compensation” was filmed in 1993, it would not be completed and screened until 1999. The film got a handful of festival prizes, and received an Independent Spirit Award nomination for Best First Feature (Under $500,000), losing to…oh man, really? [Deep exhale] It lost to “The Blair Witch Project”. Yeah, I don’t like that any more than you do.

Other notes

- “Compensation” came to be when Marc Chéry read the Dunbar poem (he was living near Dayton, Ohio at the time, where the historical Paul Laurence Dunbar House is located). At around the same time, Zeinabu Davis was working on a short called “A Powerful Thang”, in which dancer Asma Feyijinmi candidly talked about the loss of her friends and colleagues to HIV/AIDS. Davis and Chéry were intrigued by the parallels of the modern AIDS crisis and Dunbar’s death from tuberculosis at age 33, and Chéry started developing a screenplay about two love stories dealing with these two diseases.

- While attending a grant panel in Saint Paul, Minnesota, Davis and Chéry saw a production of “Waiting for Godot” featuring local deaf actor Michelle A. Banks. They were so impressed with Banks’ performance, they approached her about starring in “Compensation”. Once she accepted the part, the entire script was re-written to include Banks’ experiences as a deaf person. Neither Davis nor Chéry had any personal experience with the deaf community, and immediately began conducting research, including spending time with the Black Deaf Advocates in Chicago. It blows my mind that this film’s deaf elements were not in the original screenplay. It’s a completely different (and arguably inferior) movie without them.

- Speaking of research, you can tell that Davis and Chéry did a lot of it to present the 1910 sequences authentically. Due to budget constraints, very few locations could be dressed up to look period appropriate, so archival photos are used throughout to establish time and place. That explains why so many libraries and archives are thanked in the end credits.

- The story of Malindy being segregated and eventually expelled from Kendall School of the Deaf is based on actual events that happened to the school’s Black students. This is one of the film’s rare instances of acknowledging the racism directed at our characters in either timeline. To be fair, this movie clearly isn’t interested in being about the struggles of Black characters living in a White world, but rather about the struggles of deaf characters living in a hearing world.

- Non-verbal characters on a beach; does Holly Hunter show up in this? Oh no, am I gonna have to see Harvey Keitel naked again?

- Both of our leading actors are terrific in their dual roles: appropriately restrained in 1910, more open and affectionate in 1993. Banks in particular is captivating, with her characters’ obvious lack of dialogue being supplemented by her effective body language and facial expressions. Speaking of, it’s good to know that between Malindy and Makaila, the eye-roll has existed for literal centuries.

- John Earl Jelks is also quite good in this. It helps that Nico has a genuinely great rapport with the kids at the library, which will always endear me to any movie character. You can’t fake that.

- Marc Chéry is a public librarian by trade, so of course the handsome leading man in his screenplay works as a librarian. Coincidentally, Chéry briefly worked for Dr. Carla Hayden when she was the acting head of the Chicago Public Library. It’s all connected!

- Davis has stated that her favorite scene to shoot was the recreation of “The Railroad Porter”, the silent film Arthur and Malindy view at a local nickelodeon. “The Railroad Porter” was an actual silent film from 1912, allegedly the first with an all-Black cast and crew. Sadly, “The Railroad Porter” is a lost film, but Davis was able to faithfully reenact the film thanks to a detailed synopsis she found in her research. As you can imagine, this small part of the movie was the primary focus in the Library of Congress’ press release when “Compensation” made the NFR, to the point where I assumed it was a bigger part of the movie. Nope, just this one scene.

- A shout out to R. Kelly on the radio? Noooooo! This movie was doing so well.

- I didn’t know about the illness story beats going in, but I knew we were in trouble once Arthur started coughing. You don’t cough that loudly in a love story without it coming back later.

- Among the films Mailaika and Nico consider seeing is “Sleepless in Seattle”, which I’m still surprised isn’t on the NFR. Speaking of other movies, later on Nico is at the L train station sitting in front of a poster for “Son in Law”, which I assume is the closest Pauly Shore will ever get to making the NFR.

- The version of “Compensation” currently available through Criterion does an excellent job with the subtitles, which were supervised by Davis and Chéry for this release. Rather than just being standard closed captioning, the subtitles harken back to silent movie intertitles; fading in and out at different speeds, with occasional changes in font for emphasis. These choices help make the subtitles a part of the film viewing experience rather than any sort of distracting mandated accessibility.

- Admittedly the film lost me a bit towards the end, when Malaika and Nico separate and Nico goes on a spiritual journey to connect with his African roots. It’s all just ambiguous enough that I couldn’t figure out what was happening, but Davis has said in interviews that she purposefully left this plot line’s ending up to viewer interpretation. So…well done I guess? Side note: Great sound mixing during the breakup montage; it’s a full-on cacophony after an hour or so of leisurely silence. It really wakes you up for the last act.

- A few interesting tidbits in the credits. For starters, there are five credited ASL interpreters! Also I’m pretty sure they credit every background extra (which makes sense once you learn that almost all of them are the filmmakers’ friends and family). The Special Thanks section makes mention of both the Library of Congress and Gallaudet University, and there’s a line encouraging viewers to “[p]lease support public funding of alternative independent media!” Please let it not be too late for that.

Legacy

- “Compensation” played the festival circuit in 1999, as well as Sundance in 2000. Outside of this original festival run, “Compensation” pretty much disappeared for the better part of two decades. In 2021, the good folks at Criterion (with support from the UCLA Film and Television Archive) gave “Compensation” a 4K resolution and made the film available on their streaming service, and eventually on physical media. Most of the critical praise “Compensation” has received has been in the last five years since its reemergence and subsequent NFR induction.

- Although Michelle A. Banks has made very few on-camera acting appearances since “Compensation”, she has spent the last 30 years teaching and directing in the performing arts for both deaf and hearing children. Banks is currently the Artistic Director at the Visionaries of the Creative Arts (VOCA) in her native Washington D.C. John Earl Jelks continues acting on both stage and screen, receiving a Tony Award nomination in 2007 for his performance in August Wilson’s “Radio Golf”.

- While neither Zeinabu irene Davis or Marc Chéry seem to have any recent film credits, they are both still active in the film community, giving plenty of interviews and lectures over the years about their experience making “Compensation”. Davis’ most recent film is 2015’s “Spirits of Rebellion: Black Cinema from UCLA”, and she currently teaches Communication at UC San Diego. Davis is also one of the few NFR filmmakers to have spent a day in the Criterion Closet.