It’s that time of year again, say it with me now: National Film Preservation Board meetings regarding public nominations for the National Film Registry season! Of the thousands of films considered by the board every year for the NFR, here are the 50 I have nominated for the Class of 2025. Films with * next to them indicate films I am nominating for the first time. In arbitrary categorization, they are:

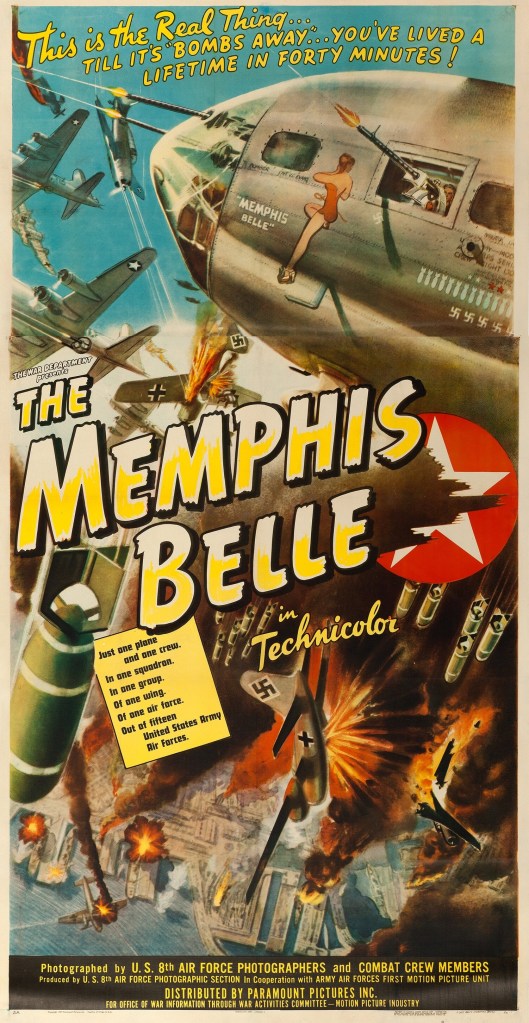

The Five-Timers Club: Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), Witness for the Prosecution (1957), The Great Escape (1963), It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963), Original Cast Album: Company (1970), Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974), 9 to 5 (1980), Clue (1985), The Sixth Sense (1999), Best in Show (2000), Hedwig and the Angry Inch (2001), Finding Nemo (2003)

Favorites: Advise and Consent (1962), F for Fake (1973), Edward Scissorhands (1990), The Player (1992), The Birdcage (1996), The Truman Show (1998), Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004), There Will Be Blood (2007)

Animation: The Jungle Book (1967), Charlotte’s Web (1973)*, Aladdin (1992)*, The Incredibles (2004)*

Classic Hollywood: Three Ages (1923)*, Animal Crackers (1930)*, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936)*, The Little Foxes (1941)*, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945), The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947)*, Royal Wedding (1951)

The David Lynch Memorial Double Feature: The Elephant Man (1980), Blue Velvet (1986)

The Peter Bogdanovich Memorial Double Feature: What’s Up, Doc? (1972)*, Paper Moon (1973)*

How Have I Gone Almost Nine Years Without Ever Nominating These?: Dial M for Murder (1954)*, Barry Lyndon (1975)*, Footloose (1984)*, Glengarry Glen Ross (1992)*, Dazed and Confused (1993)*, Se7en (1995)*, Inception (2010)*

Grab Bag: Richard Burton’s Hamlet (1964)*, Duel (1971)*, Wall Street (1987)*, Rudy (1993)*, American Psycho (2000)*, Bowling for Columbine (2002)*

And finally, New for 2025: Carol (2015)*, Tangerine (2015)*

How many of my 50 will make the final list of 25? Five? Ten? All 50? Okay, maybe not all 50, but my record is still five in one year, and it’s a record I’d love to break if the NFPB is willing.

Happy Viewing, Happy Nominating, and pleeeeease keep taking care of each other,

Tony